Click here to read the original article.

This article discusses the dangers of deflation and what we must expect from deflation today. After two generations of persistent inflation, it almost seems as though the lack of inflation today is not to be a source of worry at all, when, in fact, it should be.

America, Britain and the Eurozone are struggling to meet their target inflation, while some countries in the periphery of the Eurozone, i.e. the PIGS countries, have slipped into deflation.

One problem with deflation is that it is a self-fulfilling prophecy: if consumers believe that goods will be cheaper in the future, they will not spend now, choking consumption. If investors believe that the money they make in the future by investing now will be worth less than today’s currency, they will not invest. A lack of consumption and investment encourages deflation. As wages and incomes fall, the real value of debts will increase due to deflation.

The beginning of this deflation was the drop in oil prices. The drop in prices was because of an increase in global supply of oil by the U.S., and a decrease of global demand in oil by China, whose economy is slowing down. Generally, a fall in oil prices is celebrated; it is like a tax cut for oil importers. It is estimated to boost global growth by 0.4 percentage points.

This decrease in global demand, however, poses real problems worldwide. Inflation expectations in America, Europe and Japan have been slipping lower and lower.

There are some instances where deflation is a good sign. This is when prices drop due to a decrease in cost of production, i.e. an increase in productivity. Such “good deflation” happened to the world when they still followed the gold standard. Michael Bordo and Andrew Filardo, two economic historians quoted in this article, say that America faced such “good deflations” during the 1880’s, during which time output rose by 2%-3%.

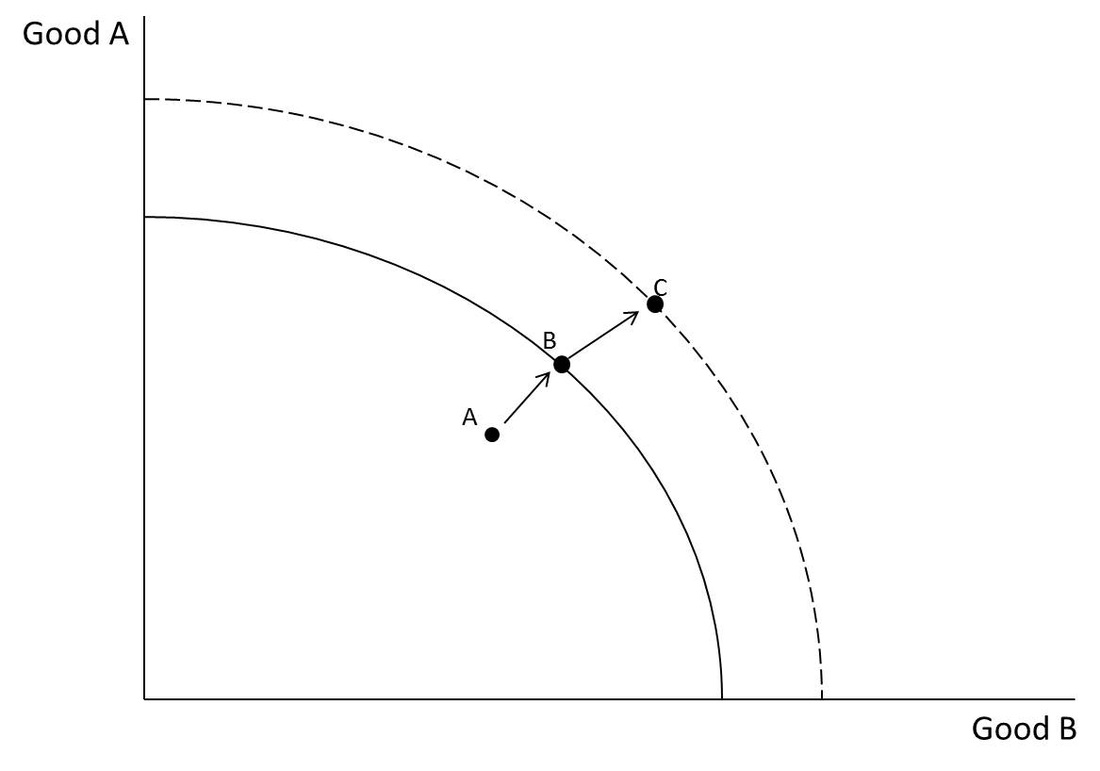

Bad deflation, on the other hand, happens when there is an output gap, i.e. demand is lower than potential supply. The result is large layoffs across the economy, increasing unemployment. Again, the real value of debt increases, which stifles consumption and investment, increasing deflation. Such a trap is called debt deflation. An example of debt deflation is in Germany, pre-WW2, a period classified mostly by Germany’s hyperinflation.

We see this bad deflation happening now. As high inflation was squeezed out of the global economy, the fear of deflation dissipated in everybody’s mind, until Japan’s economic bubble burst, slipping the economy into deflation. Japan’s economy was choking with bad debt. Economists were shocked that Japan actually slipped into deflation, as opposed to persevering with low inflation. We can see a similar assumption being made today worldwide. However, even if the world does face low inflation as opposed to deflation, the consequences are equally as severe.

Low inflation (lower than the inflation target of economies) encourages unemployment once again. Furthermore, lowflation (low inflation) in the Eurozone means deflation proper for the PIGS countries. These countries are forced to resort to internal devaluation (for more on internal devaluation, see this blog post), which exacerbates deflation.

Whether economies are facing deflation or low inflation, debt to GDP ratios are on the rise due to the lack of inflation, a ratio which was a factor in Greece’s eventual default in the Eurozone.

Secular stagnation, a phenomenon where economies need negative real interest rates to achieve full employment, becomes a very real fear as consumption and investment slow down.

In the EU, where deflation is a great problem, especially for the periphery countries, Draghi is unable to use monetary policy to alleviate the problem, facing opposition from Germany. Because of this, the euro is not being devalued. After the end of QE in America, neither is the dollar. These high exchange rates stifle exports and hence, production, exacerbating deflation.

It is no question that actual QE is needed in the Eurozone, and greater expansionary fiscal policy is needed in America (as well as in Japan!).

While these measures seem obvious, political opposition to this is abundant. They argue that it will cause debt to rise, a measure that will have to be addressed by future generations, and might cause another economic crisis.

Context:

What is an output gap? It is when the economy is not producing at its fullest potential. It can be explained by this diagram:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed