Flaws with the theory behind QE

There are a multitude of flaws with the theory behind QE. Three important ones are that QE provides diminishing marginal utility, it decreases a country’s exchange rate, and it assumes that confidence in the program is unfaltering.

1. Why does QE provide diminishing marginal utility?

David Rosenberg, Chief Economist and Strategist at Gulskin Sheff, summarized why QE provides diminishing marginal utility in the U.S.. All of the arguments cited below apply to virtually any central bank that utilizes QE as a means of economic recovery.

- Credit growth remains anemic despite massive rounds of QE. My reasoning behind this is that perhaps, at the initial stages of QE, those investors who were hesitant to borrow were galvanized by the low interest rates into borrowing; with more and more rounds of QE, fewer and fewer people borrowed as they had already done so in the past. At this stage, where the sheer volume of investors is no longer high enough to allow banks to make a profit, the extremely low interest rate dissuades banks from lending entirely; interest rates would have to be higher to compensate for diminishing volume of borrowers to allow banks to make a profit.

- The “wealth effect” people feel with an influx of money is only permanent if the influx of money itself is permanent. With the UK, talks about winding down the QE program largely dissuaded investment. Thus, increased mentions about winding QE down was met with diminishing utility with QE - people felt poorer and poorer the more winding down was mentioned.

2. What is the relationship between QE and exchange rates?

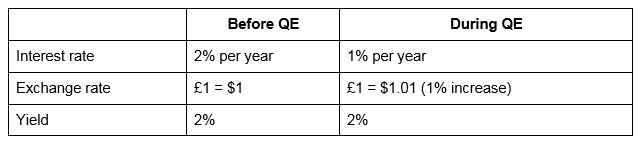

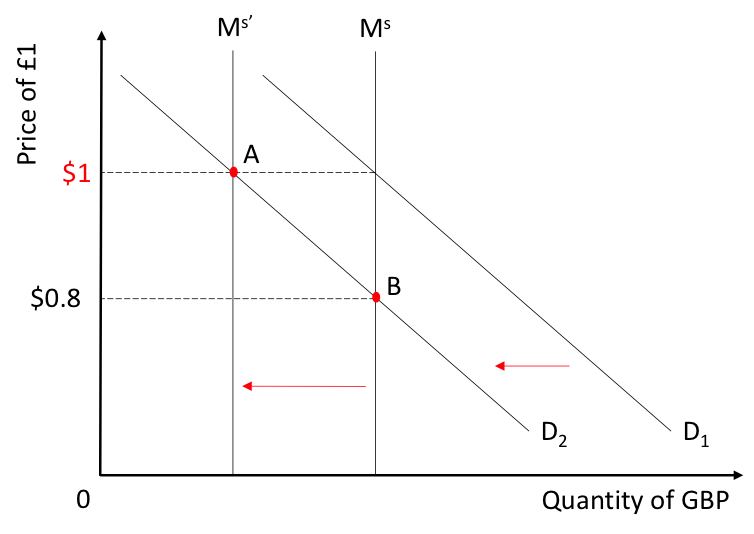

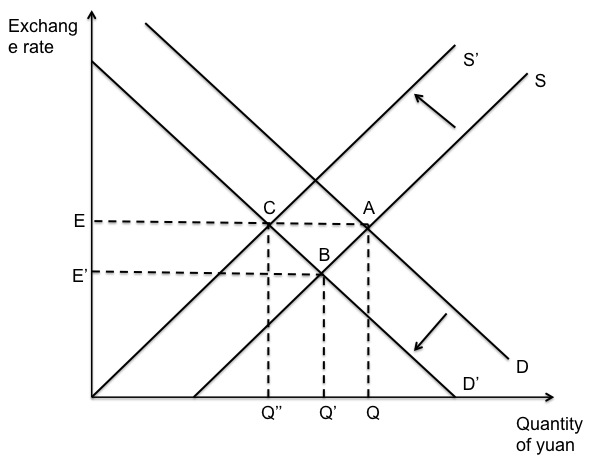

- A change in the yield due to the increased supply of money in an economy results in a depreciation of the exchange rate to maintain the yield. This is summarized in the chart below.

Assume that, before the QE program is implemented, a U.S. investor wants to invest $1 in U.K. government bonds. This process takes a few steps.

- In Year 0, he exchanges $1 for £1.

- He invests £1 in government bonds

- In Year 1, he has £1.02

- Assuming the exchange rate hasn’t fluctuated, he exchanges £1.02 for $1.02. Thus, his yield is 2% - he has earned 2% over the course of the year.

Now, assume that after the QE program is implemented, a U.S. investor wants to invest $1 in U.K. government bonds. For this to happen, he must expect the same yield; otherwise, he will not bother investing. During QE in the U.K., the interest rate has decreased to 1%. To maintain a 2% yield, the interest rate must increase by about 1%. This is why:

Assume the interest rate has changed by x%. The investor ultimately wants to make £1.02 from a £1 investment, i.e. a 2% yield. However, the interest rate in the U.K. is only 1%, i.e. the investor will only get $1.01 in Year 1 if he puts in $1 in Year 0. The extra $0.01 must then be made because of an exchange rate change.

In other words, $1.01 must now be worth £1.02 to maintain the same yield, i.e. $1.01=£1.02, or $1=£1.01.

Why is this a problem? After all, wouldn’t this increase exports and decrease imports, thus improving trade balance? Yes; however, other economies are likely to start a currency war to make their own exports competitive again.

In fact, the other problem with different exchange rates globally is that it allows for something called carry trade, a phenomenon in which an investor will borrow money from a country with a low exchange rate and invest in a country with a high exchange rate, pocketing the difference for himself.

3. Why is it wrong to assume that confidence in the program is unfaltering?

Confidence in the markets differ as different stages of QE are implemented. This one is rather self-explanatory. Depending on how international investors interpret statements made by central banks, it may lead to capital flight or rapid capital influx.

Practical problems with implementing QE

- QE encourages risky investment. Investing in government bonds itself don’t provide a high enough yield. Investors are forced to turn to riskier investments if they want to enjoy higher returns. Ultimately, it starts to sound like a situation that’s very similar to a pre-financial crisis situation: bad investments and risky behavior begets a financial crash.

- Banks find it hard to make any type of profit given the extremely low interest rates, and are somewhat dissuaded from lending. This defeats the purpose of QE entirely, where the aim is to encourage banks to lend by influxing the banks with printed cash.

- At some stage, central banks might have to start buying other assets such as corporate bonds and even equity shares. This leads to a severe distortion in financial prices and distorts the playing field.

- Asset prices increase as a result of QE for two main reasons: First, the increase in money supply for individuals must be put into something. Assets are usually a good bet due to their relative stability. Second, the low prices of assets means that people are encouraged to hold them for longer - after all, why not buy a house if the interest rate is practically 0%?

If not QE, then what?

Before discussing alternate monetary policy measures, it’s important to revisit the question, “what’s wrong with QE?”. One interpretation might be that this question is genuinely asking about the failures behind QE, some of which have been noted down already. The other interpretation of the question is a more challenging one - “what, exactly, is it that’s wrong with QE?”. Both questions are equally as important. While it is important to recognize the drawbacks of QE, it is equally as important to keep in mind that QE was the saving grace in many economies, especially the U.S.. Just because it poses problems like diminishing marginal utility now, does not mean that the same problems existed at the beginning of the program. Most economists are in consensus that QE is necessary for struggling developed economies. Without it, their economies would be suffering far past what we could imagine.

What alternatives do we have to QE? There are many, but the one most worth mentioning is helicopter money, in which there is increased collaboration between a government and a central bank to target money supply very directly. More about helicopter money will be posted soon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed