According to The Economist, in a recent report on long-term asset returns, Deutsche Bank defines a financial crisis as having at least one of the following four characteristics: a fifteen percent annual decline in equities; a ten percent fall in the currency or government bonds; a default on the national debt; or a period of double-digit inflation. In recent decades, spotting one of the four characteristics has become increasingly easy.

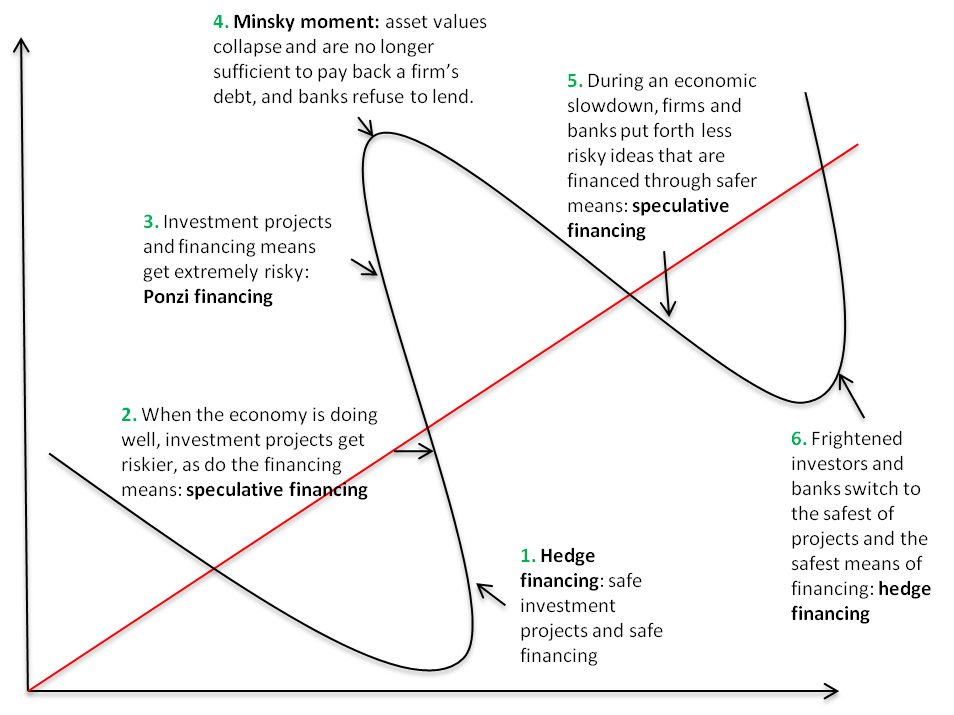

Among the prevalent theories about what causes a financial crisis is Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis, which argues that overconfidence during times of financial stability inevitably begets financial instability, and this cycle leads to booms and busts. To read more about Minsky’s theory of booms and busts, click here. Along the same lines of placing behavioral factors as the main drivers of financial crises is Robert Shiller’s theory of social contagion of boom thinking. In his book, “The Subprime Solution”, Shiller argues that booms and busts are analogous to a virus, which has a contagion rate and a removal rate (the removal rate is the point where the individual is no longer contagious). Epidemics follow when the contagion rate is higher than the removal rate.

Take, for example, the Global Financial Crisis. Feverish excitement about the property market prevailed in the US, and poorly-backed-up statements such as “property prices have nowhere to go but up” permeated most conversations about property. The prominence of such statements was confirmation of their truth to people. People then disregarded their own judgments and opinions in favor of this general information. Consequently, their contrarian views were never shared with the rest of society, and did not feature in the collective judgement. Thus, over time, the quality of group information declined. Shiller refers to this a feedback loop, in which optimism begat more optimism.

Shiller’s theory of social contagion is further aggravated by herding, where, according to John Cassidy, “at the peak of a bubble, stories of ordinary people getting rich circulate widely, exerting great psychological pressure on others to join the herd”. In a YouTube interview, Shiller elaborates on his point: “We emerged into the 21st century, believing that nothing could go wrong, and so we bought tons of houses. However, the biggest factor is our general complacency.”

The busts were similarly exacerbated by social thinking. At the height of the 2008 crash, nobody knew which bank had exposure to what bad assets, and the overconfidence and hubris that had built rapidly during the boom suddenly turned into to a lack of confidence, which was equally as contagious as the previous build-up of confidence.

Shiller also discusses in depth the role of the media in exacerbating both the booms and busts. For example, in the Global Financial Crisis, the type of stories that interested the media were the ones about poor people getting rich, instead of complicated collateralized debt obligations (CDOs, i.e. sub-prime mortgages that were packaged together and sold to investors). In an essay, Narrative Economics, Shiller explains the role of media in the Great Depression, this time on its crash: “The first narrative of the Great Depression was that of the stock market drop on October 28, 1929. This narrative was especially powerful, in its suddenness and severity, focusing public attention on a crash as never before in America.”

Concrete examples of Shiller’s theory of social contagion during the Global Financial Crisis are abundant. Take, for example, the Icelandic Financial Crisis, and Ireland’s financial crisis. Iceland is a small island and was very closely networked, both socially and politically. There was no one in either politics or business that did not go to the same school or mix in the same circles. This provided a fertile ground for social contagion of thought patterns, which perpetuated the belief that markets could only go up, leading the Icelandic banks to assume ever greater amounts of debt in pursuit of profits. The close interconnectedness of the Icelandic economy meant that the feedback loop was quicker and more vicious.

Ireland, like Iceland, was a small island that was characterized by homogeneity. The small size of the country ensured that politicians and financiers knew each other well, and were thus rendered subject to herd behavior. The media in Ireland exacerbated the boom it faced: it had close ties to the property market, and consequently, huge incentives to keep up property prices. According to Shiller, the media talked up the boom, and the bust was consequently much rougher.

In all previous crises, we have seen telltale signs of financial stability breeding instability, and social contagion causing booms and busts. These have been constant factors in the human nature, but still we see more crises in the last few decades than ever before. Why is there an increasing number of financial crises?

Deutsche Bank argues that the answer lies in the monetary system. Before the early 1970s, when the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system was in place, money creation was limited. A country that increased its supply of money too quickly faced inflation. This led to the price of exports increasing, which led to a decrease in exports, which led to exchange rate depreciation, which led the central bank to no longer expand money supply too quickly. In other words, it was hard for financial bubbles to form, given the central bank’s control over money supply.

However, following the abolition of Bretton Woods in the early seventies, most developed countries switched to a floating exchange-rate regime. This new system allows them to not “subordinate other goals to maintaining a currency peg” (to see a central bank’s goals in relation to a currency peg, read this article on the Mundell-Fleming trilemma). This allows for greater trade imbalances, as the currency can bear the burden of it – at least for a while.

These problems are reflected in government debt, which, since floating rate regimes, has been rising as a ratio to GDP. Governments find no pressing reasons to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio: according to The Economist, “Japan has had a deficit every year since 1966, and France since 1993. Italy has managed just one year of surplus since 1950.” Consumers and companies, as well, have been taking on more debt as well.

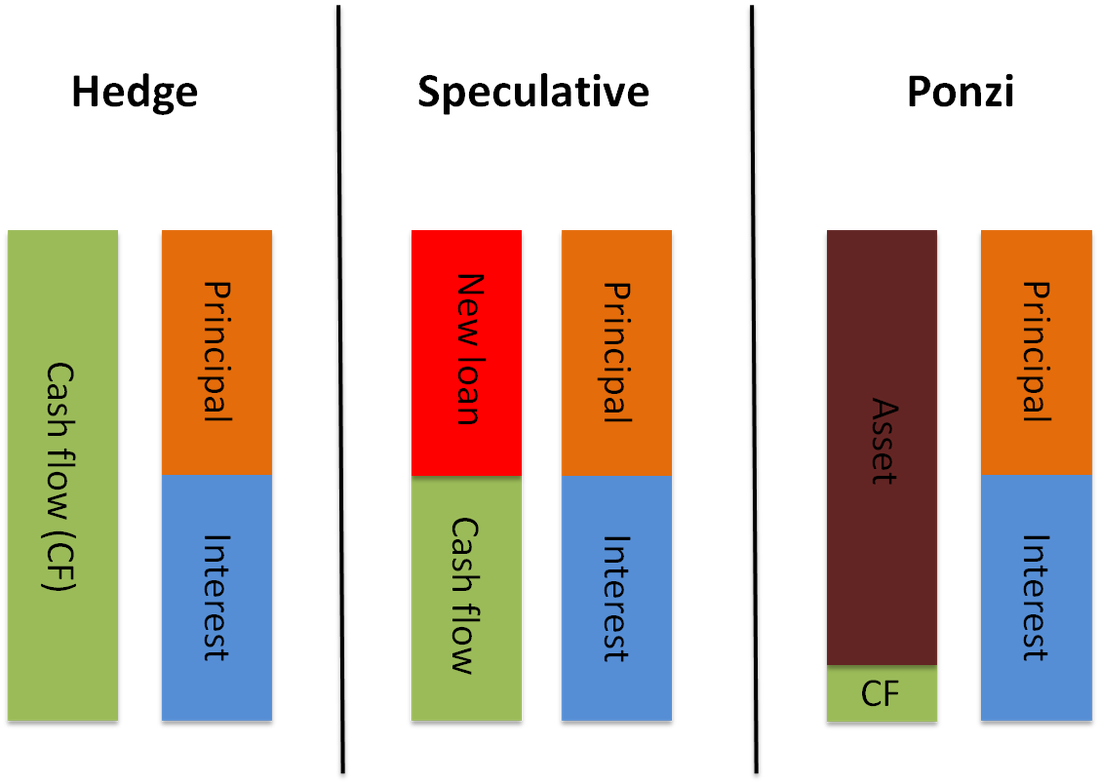

This is especially worrying. In previous crises, such as the Global Financial Crisis, debt has financed the purchase of assets to cause an upwards spiral, i.e. a boom, and this similar downwards spiral can happen during a bust. To understand the role of debt in a bust, it is important to understand leverage. Leverage is the degree to which an investor is using borrowed money as opposed to his own funds (equity).

Consider, first, an asset bubble. Assume an asset price goes up. This enables investors to borrow more against the assets, while maintaining the proportion of debt. In fact, encouraged by the rising asset prices, lenders are willing to raise the proportion of debt. With the additional debt available, investors are able to buy more assets, raising the asset prices further in an upward spiral.

A similar process in reverse happens during the deleveraging stage. In fact, the longer the deleveraging cycle persists, the worse the situation gets. During deleveraging, firms usually sell the easy-to-sell assets that are the most liquid. The longer this goes on, the worse the quality and liquidity of the remaining assets.

A sudden fall in asset prices during a deleveraging cycle does not happen randomly: it is often caused by an external event. CNBC refers to the Deutsche Bank report, and cites a multitude of potential triggers for a fall in asset prices, if we are, in fact, in an asset bubble. Among these triggers is a potential Italian crisis. Deutsche states: "A country nearing an election and with high populist party support, with a generationally underperforming economy, a comparatively huge debt burden, and a fragile banking system which continues to have to deal with legacy toxic debt holdings ticks a number of boxes to us for the ingredients of a potential next financial crisis." Other triggers that Deutsche has cited are Brexit, and a rise in populism.

If we are in a bubble, then we can expect to see a bust in the coming years. If this is the case, central banks must have enough tools to protect the economy from this bust. As a reaction to the crisis, in 2008, central banks cut interest rates and bought assets directly in a mechanism known as quantitative easing. This stopped the previous crisis, but each boom and bust cycle has reflected higher debt levels and asset prices. Now we see that the combined valuation of bonds and equities in the developed world is at its record high.

If this really is the case, all evidence points to a debt-related boom-and-bust cycle. If we are in an asset bubble, we should be able to see the social contagion of thinking exacerbated by the media, as well as risky investments replacing safe ones. In the next article, I will look at signs that we are currently in an asset bubble, including the prices of stocks, equities, and property.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed