Click here to read the original article.

What is international macroeconomics?

The Mundell-Fleming trilemma is rooted in international macroeconomics, which is the study of policymaking decisions that affect how global economies interact with one another. International macroeconomics deals with issues such as balance of payments, trade agreements, and capital controls.

What is the Mundell-Fleming trilemma?

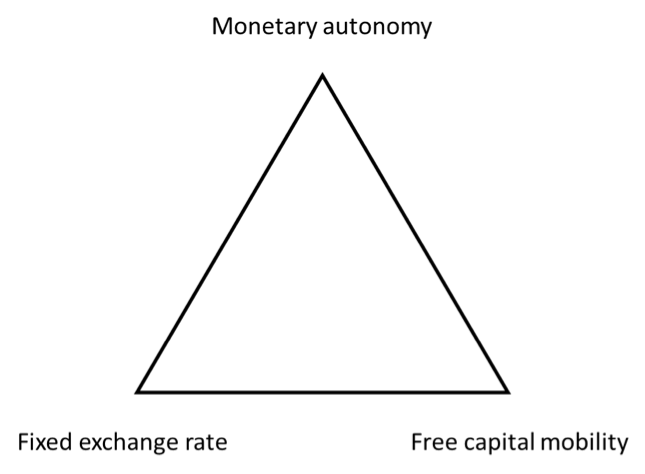

The Mundell-Fleming trilemma is described as the essence of international macroeconomics, according to Michael Klein from Tufts University. It states that, given the choice between monetary autonomy (explained under ‘Context’), free capital mobility, and a fixed exchange rate, an economy can only choose two of them. The trilemma is represented below.

For example, let’s take an economy that decides to maintain both monetary autonomy and a fixed exchange rate.

Assume the U.K. has its interest rate set at 2% a year, and its exchange rate is at parity with the U.S. dollar, i.e. $1 will get you £1. The U.K. decides to fix its exchange rate such that it is always at parity with the U.S. dollar.

Given this scenario, U.S. investors convert $10,000 a day to £10,000 and invest it in the U.K. economy. Now, assume that the Bank of England wants to decrease interest rates in order to encourage British investment in the local economy: the interest rate falls to 1%.

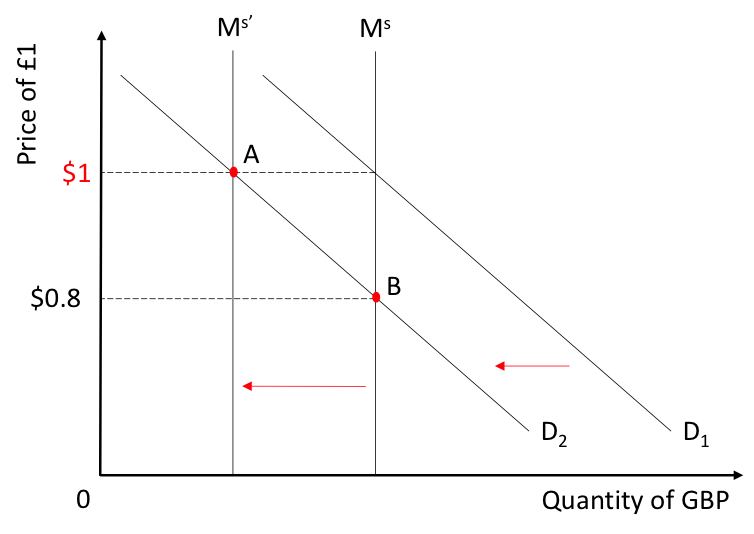

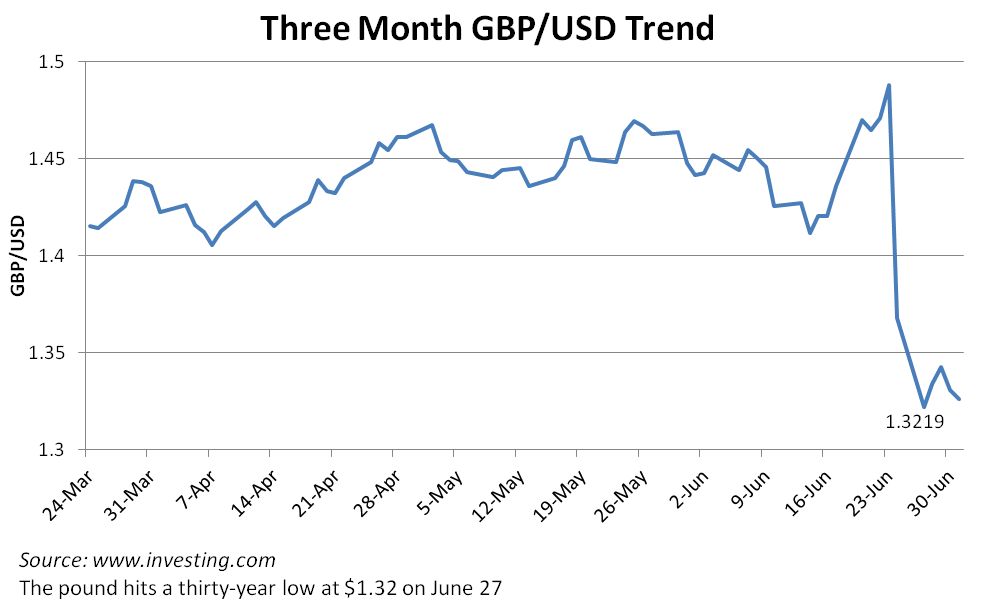

U.S. investors now feel less inclined to invest as much money as their return has decreased by 1%. Thus, they want to convert fewer U.S. dollars into the British sterling, i.e. the exchange rate falls. This is illustrated below.

Forsaking a fixed exchange rate

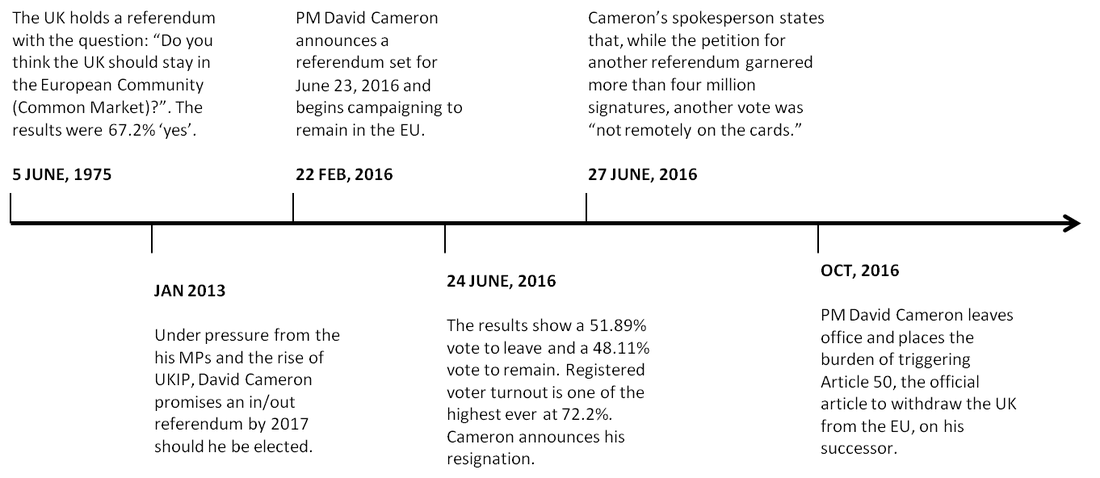

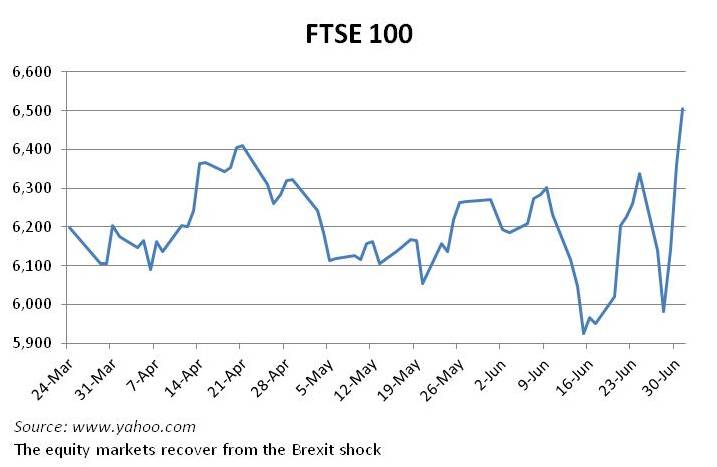

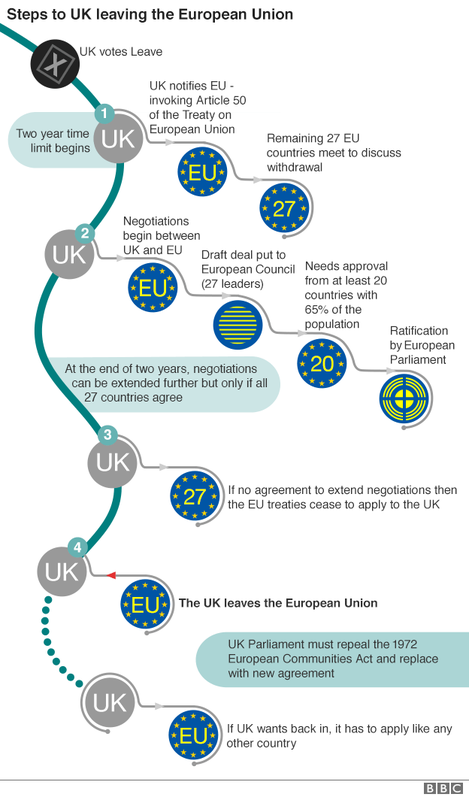

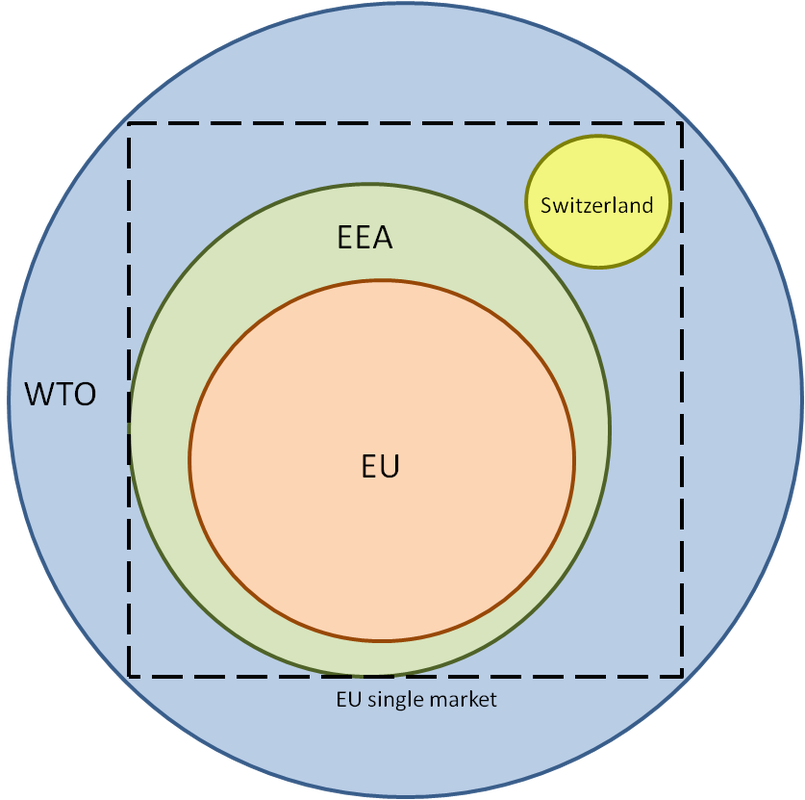

If an economy decides it wants monetary autonomy and free capital mobility, it will have to give up control over its exchange rate. Assume that a certain event in the U.K., such as Brexit, has caused panic amongst international investors. They withdraw their financial capital (such as money) due to uncertainty over the future of the British economy, which depletes the U.K.’s reserves of foreign currency. Without the Bank of England’s increasing interest rates to encourage capital influx, foreign reserves stay low. Without these reserves, the U.K. cannot maintain a fixed exchange rate (explained under ‘Context’), and must allow its exchange rate to float.

Forsaking monetary autonomy

If an economy decides to maintain both a fixed exchange rate and free capital mobility, it must forsake monetary autonomy. To maintain a fixed exchange rate, the U.K. must have a certain level of foreign reserves, i.e. it has to ensure that foreign investors are incentivized to invest in the British economy, which would maintain the level of foreign reserves. If it wants to allow capital to move freely between borders, it must set an interest rate high enough to encourage a certain level of foreign investment. In other words, the U.K.’s interest rate must be determined by the amount of foreign reserves it requires to maintain a currency peg.

An example of a currency peg is the Hong Kong dollar, which, since 1983 has been pegged to the U.S. dollar at a rate of US$1 = HK$7.80. Between 1974 and 1983, the Hong Kong dollar was allowed to float. In 1974, the U.S. dollar depreciated, which encouraged capital influx to the U.S., and consequently, capital outflows from Hong Kong. As Hong Kong chose not to stem capital outflows, it had to choose between allowing its currency to float and forsaking monetary autonomy. Until 1983, it chose the former. To read more about the history of the Hong Kong dollar, click here.

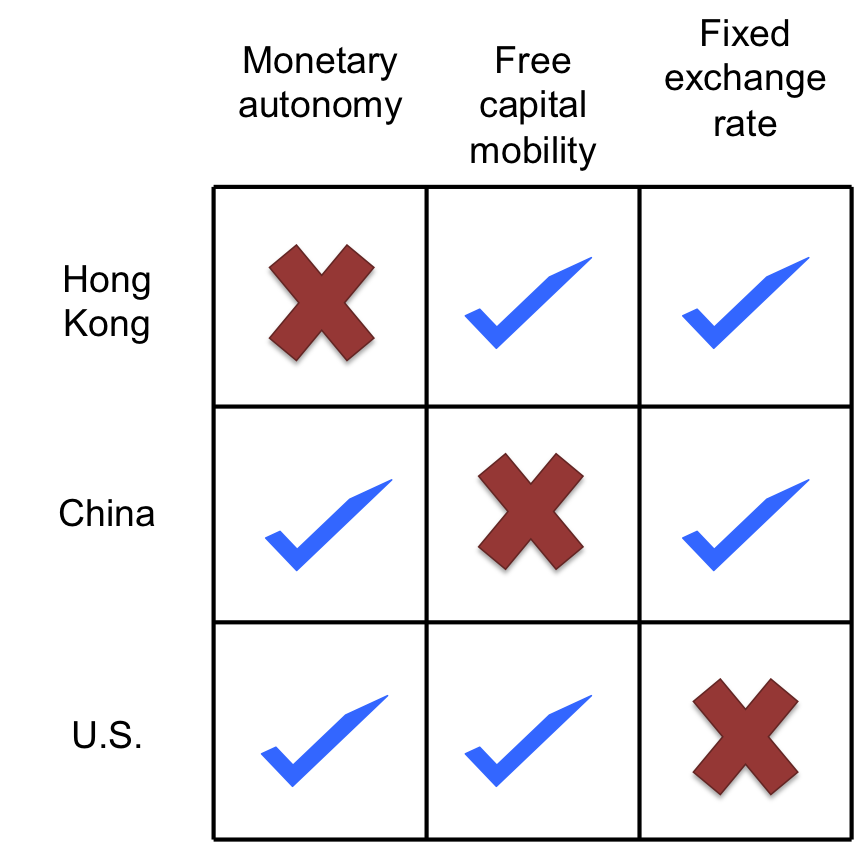

The trilemma and the EU

The Euro was first launched in 1992, under the Maastricht Treaty. In order for an economy to participate in the Euro, it had to fulfill six conditions, one of which was to have an interest rate set close to the EU average. In the run-up to the establishment of the Euro, economies fixed their currencies to the Deutschmark (the currency used earlier in Germany) and allowed their capital to move freely across borders. The participating European economies then relinquished monetary autonomy and followed Germany’s interest rate closely. Wim Duisenberg, the head of the Dutch central bank, was dubbed “Mr. Fifteen Minutes” due to the alacrity with which he copied the interest rate decisions of the Bundesbank, the German central bank.

Today we can see the implications of a single interest rate in the EU. For economies that followed Germany’s business cycle back when the Euro was first established, such as the Netherlands, there was little impact of copying Germany’s interest rate. However, for economies that did not parrot Germany’s business cycle, such as Greece and Spain, interest rates were too low during booms, which caused major troubles when their economies faced busts.

After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the EU was hesitant to embark upon QE, a policy that necessitated lower interest rates across the common market. Even though it would have helped the suffering PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) economies by encouraging domestic investment, Germany voiced its hesitance, stating that it would leave Germany vulnerable to hyperinflation. Determining an interest rate that placates all members of a common market has proven to be nearly impossible.

The history of the trilemma

The first mention of some tension when it comes to international macroeconomic policymaking was by J.M. Keynes, who, in his 1930 essay “A Treatise on Money”, stated that “[preserving]… the stability of local currencies… and [preserving] an adequate local autonomy for each member over its domestic rate of interest and its volume [poses a dilemma]”.

This dilemma (Keynes assumed free capital mobility) was the basis of Keynes’ criticism of the interwar gold standard: trade imbalances forced deficit countries to raise interest rates and lower wages to stop the hemorrhage of capital, which led to mass unemployment. If surplus economies increased their imports, this problem would be self-solving, but no surplus economy had any mandate to do so.

In the Bretton Woods conference, Keynes proposed a solution in which an international clearing bank (ICB) aids with deficits and dissuades surpluses. Unsurprisingly, this idea faced great opposition from America, which was an economy with a large trade surplus. The ICB was abandoned, but the idea of an international bank aiding deficit countries became the basis for the IMF.

Marcus Fleming was in touch with Keynes when he wrote his paper on the impotence of monetary policy in the face of a fixed exchange rate and freely-moving capital. Independently, Canadian economist Robert Mundell reached a similar conclusion, but was inspired by different circumstances.

Years after the Second World War, there were scarcely any countries that faced rapid and free capital mobility. Canada was an exception: it allowed capital to travel freely through its border with America. Because it valued monetary autonomy highly, it had no choice but to let its currency float from 1950 to 1962.

Maurice Obstfeld, the current Chief Economist of the IMF, was the first one to mention the term “policy trilemma” in a paper he published in 1997. Since then, the trilemma has become a centerpiece of macroeconomic textbooks, and a conversation piece for international policymakers.

Why the trilemma matters

International trade and globalized economic activity became increasingly commonplace after the Second World War. Economies that had to deal with sudden capital flight or influx, or struggled to maintain control over their currency, had to turn to a previously-ignored idea to not only understand why they did not have as much control over their markets as they did before the war, but also to understand how to deal with it and what the opportunity costs of choosing certain policies were.

The Mundell-Fleming trilemma paved the way for conversation about policymaking with reference to international economies. Today, we notice the impact of all policy decisions on global economic activity: divergence in terms of QE policies between the U.S. and Japan might lead to carry trade; China’s maintaining both monetary autonomy and a strongly-managed exchange rate means that it must employ capital controls; the Bank of England’s decision to continue with QE resulted in a depreciation of the GBP.

A criticism of the trilemma

A big critique of the Mundell-Fleming trilemma has been provided by Helene Rey, from the London Business School, who stated that an economy that allows both capital flows and a floating exchange rate will not necessarily have control over its monetary policy. To hear her lecture on why, click here.

Context

1. What is monetary autonomy?

Monetary autonomy denotes a central bank’s ability to choose its policies, especially interest rates, without taking into account the impact of its interest rate on international markets.

If a central bank has to take into account the reaction of international markets due to an interest rate decision, it would be because higher interest rates would encourage investors to purchase local government bonds, leading to capital influx. Alternatively, lower interest rates would lead to capital flight.

2. Why does a fixed exchange require lots of foreign reserves?

A central bank that wants to peg its exchange rate must meet decreased demand for its currency by lowering the stock of its currency in the forex market, and increased demand by increasing the stock of its currency in the forex market.

To increase the stock of its currency, a central bank must buy foreign currency using its own currency. Conversely, to decrease the stock, it must buy its own currency using foreign currency, which means that it should have a stock of foreign currency to do so.

An economy must have enough foreign currency in its reserves to have the full flexibility to both buy and sell its own currency. Hong Kong, for example, has a large stock of foreign reserves to maintain its peg to the U.S. dollar. For this reason, speculators do not attack the Hong Kong dollar.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed