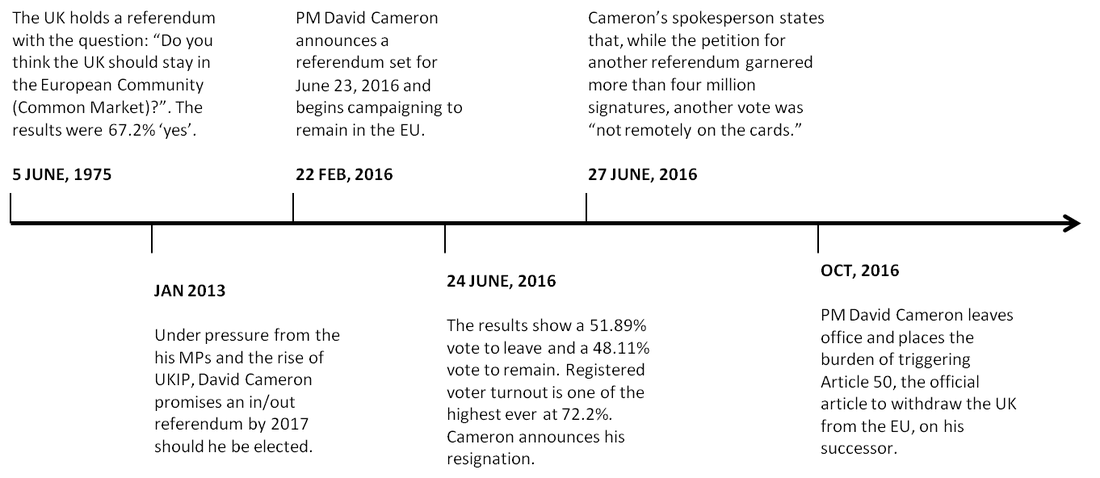

The UK’s decision to leave the European Union (EU) surprised both Leave and Remain supporters alike - not to mention, the rest of the world. Whatever decisions the UK’s new prime minister will take, Britain will still be stepping into the unknown. With an unclear future ahead, everyone seems to be asking the question nobody has the answer to: what next?

On trade and the economy:

- Leave supporter Ian Duncan Smith promises £350 million per week contributed towards the EU budget would be redirected to the National Health Service should the UK leave. In fact, most of this £350 million is returned by the EU through various payments, and the Leave party has since reneged on its promise.

- Leave cites an abundance of red tape due to the EU’s many product regulations as a barrier to trade.

- Remain states that uncertainty and a reduction of trade if the UK leaves would result in decreased growth, if not a recession, a statement met with general agreement among economists.

- Leave claims that EU members, especially the Poles, are taking away British jobs. Remain argues that it is free movement of labor that guarantees healthy competition and that only the more skilled workers get UK jobs.

- Leave argues that without forced cultural assimilation, Britain will face more and more pockets of impenetrable cultural bubbles.

The Financial Times highlights five key demographics.

- Areas where more people had a degree voted to remain.

- Areas with a small number of people in “professional occupations” voted to leave.

- Areas where more people had passports voted to remain.

- Lower income areas voted to leave.

- Older people voted to leave.

Immediate reactions

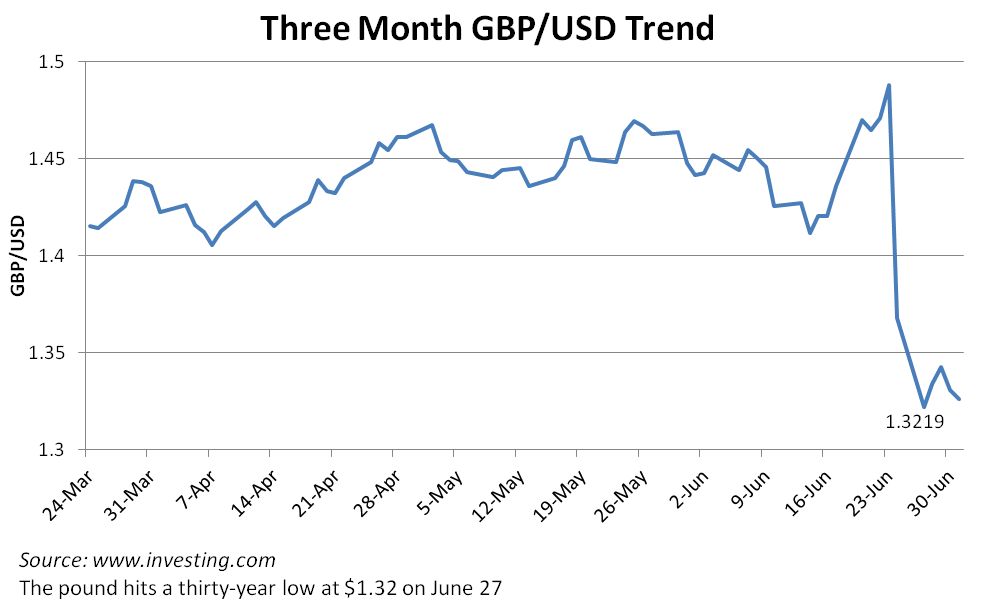

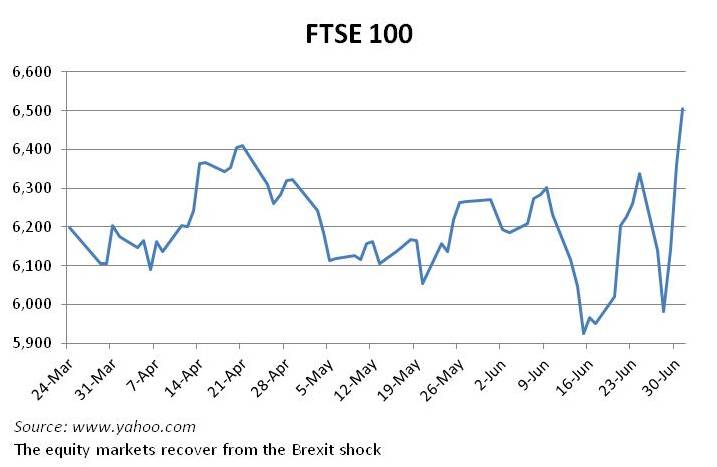

After the shocking results of the EU referendum nearly a fortnight ago, it is no surprise that both UK and global financial markets reflected the sentiment of uncertainty. Most notably, the pound briefly dipped to a thirty-year low at $1.32 on June 27th, far below its pre-referendum high at $1.50. This drop is somewhat a relief as it dissuades imports and encourages exports in the UK. Equity markets, on the other hand, have bounced back above their pre-referendum levels. According to The Economist, this is due to the “oil and mining giants… [having] little to do with the British economy.”

Standard and Poor’s (S&P) downgraded Britain’s AAA rating to AA, and Fitch Ratings downgraded them from AA+ to AA. Moody’s has lowered its outlook for the UK from stable to negative.

S&P also lowered the EU’s credit rating from AA+ to AA.

What next?

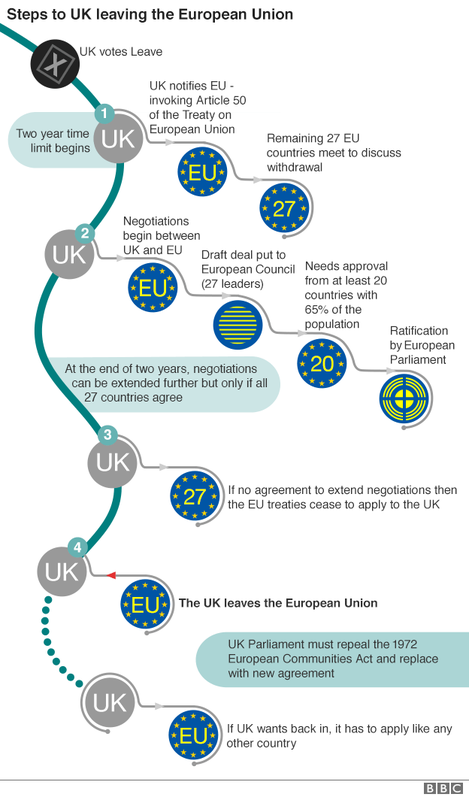

Starting with the practical aspects, the BBC outlines the process for the UK to leave the EU.

In terms of trade agreements with the EU, the UK has a few choices:

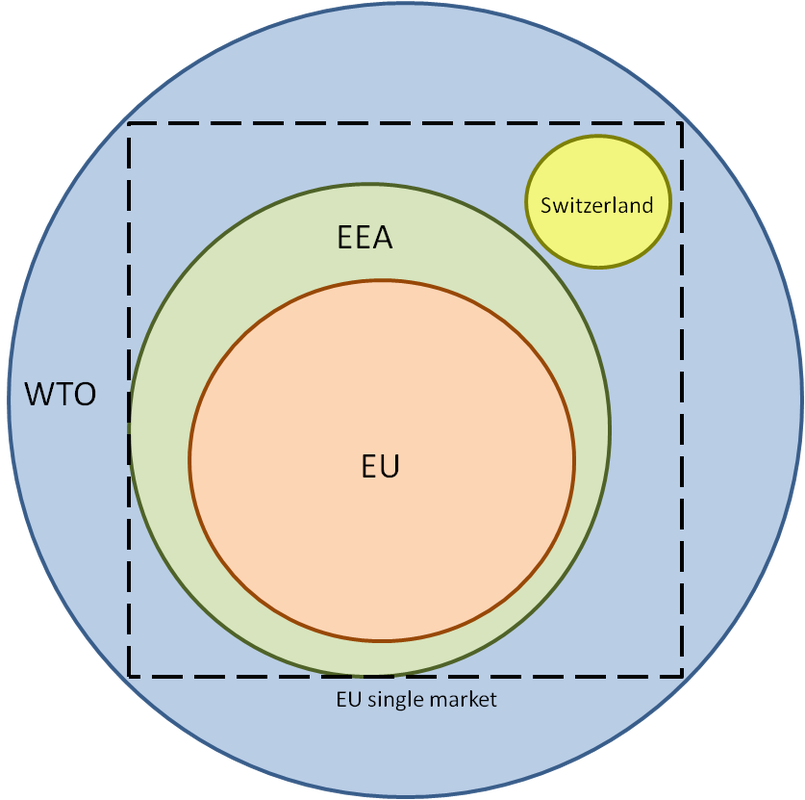

Some suggest that the UK might stay in the European Economic Area (EEA). The EEA allows its members to participate in the EU’s single market. Countries that are in the EEA but not in the EU include Iceland, Leichtenstein and Norway. It is unlikely that the UK will remain here, as the single market requires the free movement of labor.

The only country that is not in the EEA but is still in the single market is Switzerland. It is unlikely that the UK will aim for a position like Switzerland as the single market means immigration.

If the UK does not participate in a special trade agreement with the EU, it will trade with the EU under global trade laws dictated by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Some Remain campaigners had suggested that if the UK leaves the EU, the EU would retaliate with tariffs. It is important to note, however, that under WTO laws, retaliatory tariffs are not allowed.

Regardless of whatever trade agreements are decided upon, unless the UK decides to somehow remain in the EU, it is likely that Scotland will hold a referendum to leave the UK, and quite possible that Northern Ireland might do the same. Both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. After the 2014 Scottish referendum was held to see whether Scotland would leave the UK, where ‘no’ was 55% and ‘yes’ was 45%, dissatisfaction with the UK has been steadily mounting, hitting a high when the UK voted to leave the EU. Informal talks about a second Scottish referendum are currently being held.

Undoubtedly, if Scotland does leave the UK, the British economy will suffer. However, most economists believe that the UK will suffer for a while regardless. Uncertainty continues to exacerbate the exchange rate depreciation. There is the possibility that London might lose its position as a global financial capital, leading to a shrinking of the financial sector, while the other countries in the EU will try to establish their own cities as the leading contenders for that role.

A majority of economists believes that the UK will be facing a recession either in the coming year or the next. Not all economists are as pessimistic – some believe that if the UK takes this opportunity to create strong trade agreements with other nations, Brexit will have a neutral, if not positive, effect on the UK economy.

To dispel the uncertainty, the Bank of England, as well as the government, must themselves have a clear plan of action, whether it is the Bank of England clearly outlining what steps it will take to begin monetary easing, or the new prime minister leaving little doubt regarding his or her plan for invoking Article 50. A clear plan on how they will proceed, economists say, will reassure the public that control of the economy is still in the hands of the UK. In fact, Carney has already promised the British public that the central bank’s monetary policy will be paired with “ruthless truth telling”.

A more disturbing message from the Leave campaign unveils not only how Britain will be in the years to follow, but the rest of the world as well. Much of the Leave campaigning promotes anti-immigrant sentiment, whether it be job displacement or cultural dilution. In fact, the likeness to Trump’s campaign is startling: he, too, blames immigrants for job losses, not to mention terrorism.

In this way, fear of globalization is a by-product of globalization. A wave of immigration might give the public a feeling of domestic job displacement, to which they will respond with anger against immigration. In a larger sense, these fears are not unreasonable – after all, many of the displaced domestic workers struggle to find jobs and receive little aid from the government. While this is not a reason to slam the borders to immigration shut (globalization provides many advantages such as increased skill and productivity, resulting in increased GDP), it is a call for governments worldwide to not only battle the fear but provide better systems to deal with displaced workers.

At this point, not enough time has passed after the EU referendum for the waters to settle. In a few months, we will know more about the possible shape of the economy, and less will be left in the hands of uncertainty.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed