This article discusses the effects of and the lack of potential solutions to the current worldwide deflation.

Christopher Sims, a Nobel laureate who specialises in causality in macroeconomics (quoted in this article) warns that QE by itself has little effect on monetary patterns, and thus, on inflation. He says that the only reason Anglo-Saxon QE worked at all is because the central banks (BoE and the Fed) “talks a better game” (which, in its essence, is qualitative easing) than the ECB.

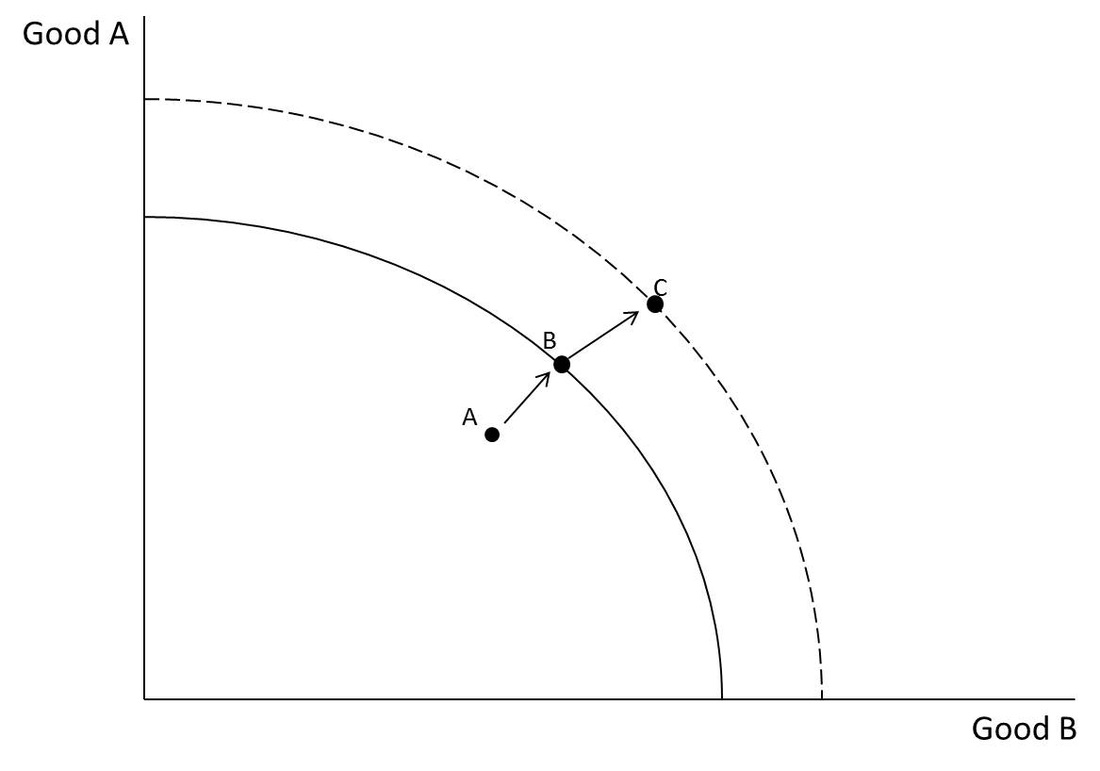

The effects of deflation are:

1) Pre-emptive retrenching, given consumer expectations for prices to decrease.

2) Decreased investments and increased savings from businesses who expect a hit.

Overall, the two points above mean that there will be less money circulating the economy. Notice how those two points show that an expectation of deflation causes deflation – these two reasons are the main reasons why deflation is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Whether QE works to increase deflation can be seen by observing Japan, whose large-scale bond-buying programme is meant to encourage inflation.

Key words:

1) Money indicators: money indicators measure the amount of money in an economy. Different definitions of money supply include cash, or cash and deposits, or checks.

These definitions, according to Investopedia, are:

a) M0: Hard cash and coins

b) M1: M0 + checking accounts, traveller's checks, demand deposits

c) M2: M1 + savings accounts, time deposits (less than $100,000), money market funds

2) Primary surplus: This is where government income – government expenditure > 0 but the interest on the loan has not been paid back yet. For another blog post that discusses the primary surplus, click here.

Context:

What is Sims referring to when he says that the Fed “talks a better game” than the ECB? This is the idea of qualitative easing (more can be read about this here), where the Fed assured the economy that it will do its best to decrease unemployment and increase inflation, i.e. they said that they would carry QE through to the end. I disagree that the ECB doesn’t “talk a good game”. In fact, in 2012, Draghi said that the ECB will “do whatever it takes” to improve the economy. In 2012, many people believed that the periphery Eurozone countries would split from the EU. As a result, borrowing rates for the PIGS countries increased, and confidence in the euro was lost. Draghi responded by saying that the ECB would do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. Because of this, the faith in the Euro was restored and the borrowing rates for the periphery countries dropped. Click here to read the official statement made by Draghi.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed