This post combines two articles by The Economist. Click here and here to read them.

These two articles discuss the current problems China is facing, potential solutions and its consequences.

China has been showing cracks in its economic structure for the past six months, and with the stock markets crashing on January 4 2016 and an increased debt-to-GDP ratio of about 300%, the problems with the Chinese economy are now being closely watched by everyone. According to the article “Rocks and Hard Places” (RHP), however, it is the foreign exchange market that bears watching for those wishing to know about the state of China’s economy.

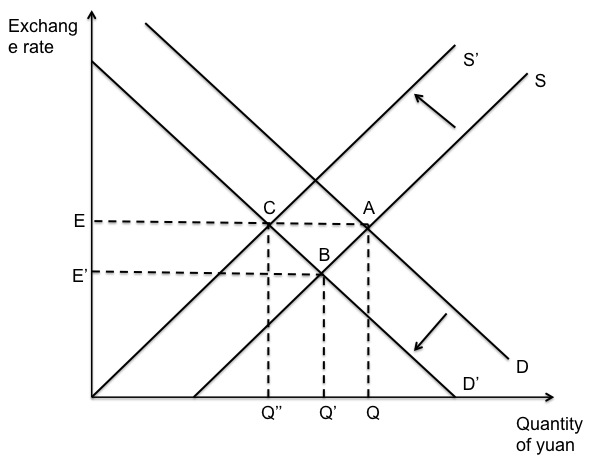

China’s pegged exchange rate is much higher than its exchange rate would be in a floating system, and many believe that devaluing the yuan and bridging the gap between the real exchange rate and the current one would ameliorate the economy.

Asian countries during the Asian financial crisis faced a similar predicament to the one China is facing – According to “Fight or Flight” (FF), investor outlook turned from bullish to bearish, resulting in a great outflow of capital. Thus, reserves dwindled and the governments could no longer maintain a pegged currency. The key difference between those Asian countries and China is that China has, and has had for a while, tight capital controls. According to FF, during China’s great boom in the 2000s, foreign direct investment (FDI) was permitted while hot money was tightly controlled.

These preventive measures did not stop the depletion of China’s reserves – now down to $700bn, “thanks to capital flight and sinking asset values” (FF). An increase in China’s outward FDI paired with a decrease in inward investment resulted in the lowest net flow of inward investment since 2000.

While China wishes to impose tighter capital controls to prevent a dwindling of reserves and tightening of domestic credit (explained in ‘context’), there is “no painless way to do so” (FF).

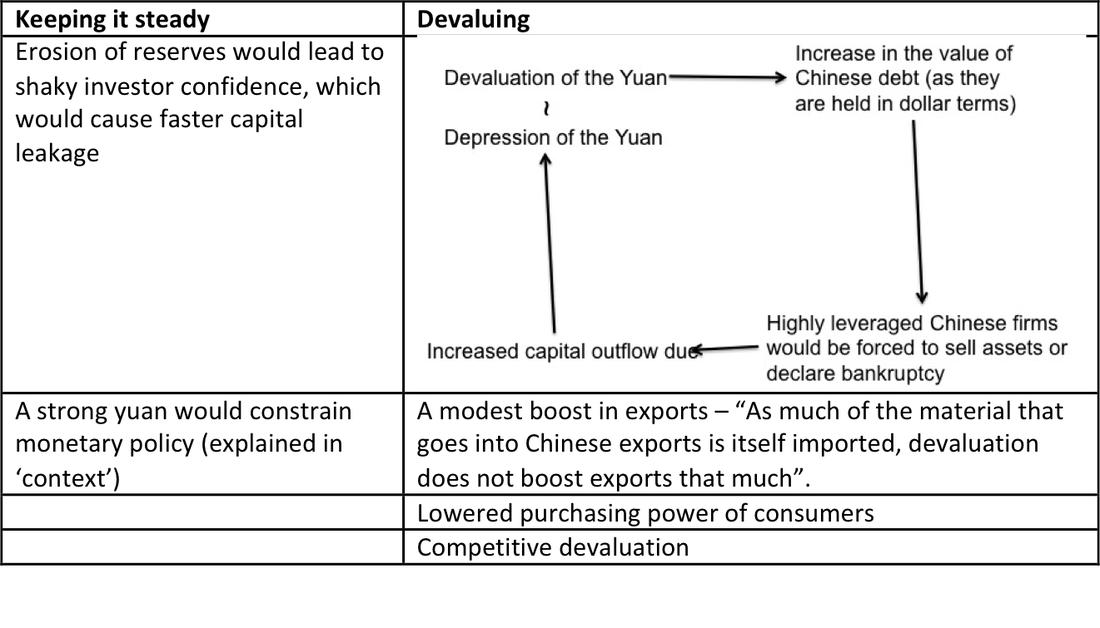

In terms of exchange rates, the Chinese can either keep the exchange rate steady or devalue the exchange rate. Keeping the exchange rate steady is a feasible option as China has $3.3tn in reserves. Here are the consequences for either action:

However, according to RHP, these trade-offs to rebalance the Chinese economy are only short-run. Strengthening capital controls by locking down the capital account in the long-run could be vastly beneficial: free from the pressures of the global markets (explained in ‘context’), the government could “clean up bad debts and push through structural reforms needed for long-run growth”. In fact, locking down the capital account would result in unfreezing those accounts during a time when the Fed is not raising interest rates, which would deter investors from moving their money to the U.S.

Chances are, however, that if capital accounts were locked, the government would do little to implement structural reforms but would instead use it as an excuse to “rollover bad debts and delay reform” (RHP), i.e. following the Japanese path (explained in ‘context’).

In fact, despite the fact that locked capital accounts would allow for more flexibility in China’s monetary policy, the government “would find itself cornered” (RHP): once interest rates and reserve ratios were near zero, QE would lead to a further imbalance in the economy. The government would have to respond with massive fiscal stimulus or depreciation to allow for further monetary policy, all of which are irreversible actions for a few generations to come.

Instead, China may have a slightly less bitter pill to swallow. Given its capacity for lots of fiscal stimulus (government debt is low; thus, the government has room to borrow and then spend), it could force banks to “recognize bad loans, close insolvent businesses, and use that capacity to ease the pain on creditors and shore up banks” (RHP). This, still, may result in a sharp slowdown of growth, and perhaps even a recession. However, these are pills that other countries have followed and survived through. The question is whether the Chinese government was built to cope with such drastic measures (explained in ‘context’).

At the current time China is not facing an imminent crisis. It has “ample reserves, capital controls, trade surplus and a determinedly interventionist state” (FF). Increased purchase of foreign securities may, in fact, decrease the effect of depreciation on debt (explained in ‘context’). However, it remains that should China ever come to face such a crisis, its results would be disastrous.

Key Terms:

1. Capital account: a sum of private and public investment flowing in and out of a country.

2. Reserve ratios: a ratio of all deposits into a bank that must be held by the central bank. China’s reserve ratio is currently at 7.5%.

3. Bullish vs. bearish: Bullish means upward trending while bearish means downward trending.

4. Hot money: money that can be liquidated immediately. This is unlike FDI, which can be liquidated after a set amount of time (usually a few years).

5. Hard currency is the name for dollars, euro, yen, i.e. the more important currencies.

Context:

1. What is the relationship between reserves and a pegged (or fixed) exchange rate? An exchange rate is pegged by the central bank’s buying or selling the domestic currency.

Thus, if China wishes to maintain its exchange rate, it must keep selling off its reserves, i.e. a depletion of reserves.

2. Why is there capital flight in China? This is because of investors’ fear that China is slowing down and their subsequent wish to withdraw investments from China and invest elsewhere.

3. Why do tighter capital controls lead to a “tightening of credit”? The amount of bank deposits will decrease, so banks cannot make as many loans; thus, credit conditions tighten.

4. If a decrease in exchange rates would not increase exports, why did China do so well during its more prosperous periods? When China faced good growth, it wasn’t the devaluation of the yuan that made it so successful (the yuan held steady). At that stage, there was enough capacity for exports to grow, with enough demand. After the GFC, China could not export as much because of decreased demand. They turned to investment, which is now faltering.

5. Why does purchase of foreign securities “hedge firms with foreign-currency debts against depreciation”? If firms have foreign currency debts and the currency depreciates, the debts increases. If firms have foreign assets, then it would reduce the impact of the debt.

6. Why would locking down the capital account free China from the “pressure imposed by global markets”? Without the capital lockdown, at sight of a higher interest rate in the U.S., investors would take their money from China and invest in the U.S., but with the capital lockdown, whatever the global market decisions are, a certain amount of investment stays in China.

7. How would China follow the Japanese path should they fail to implement structural reforms? Before Japan’s deflationary spiral, Japanese banks had bad debt and didn’t have them written off, leading to deflation.

8. Why would China not be built to deal with the drastic measures proposed by The Economist? The problem is that China is communist: they’ll give people jobs, security, etc. as long as they don’t question the government. A loss of jobs thus leads to a criticism of the Chinese government, a risk China may not be willing to face due to fear of political reform.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed