Click here to read the original article.

Mr. Piketty, along with a handful of other economists, has gathered data from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution about the change in the concentration of income and wealth. During the 18th and 19th centuries in Western Europe, wealth inequality was rampant. National income was less than private wealth, the latter of which was concentrated in the hands of the elite few. Even when industrialisation increased the wages of the working class, this problem persisted. When WW1, WW2 and the Great Depression hit, the inequality of income and wealth reduced, due to high taxes, inflation and bankruptcies. After these shocks faded, the same problems are creeping back, so much so that the importance of wealth is reaching levels pre-WW2.

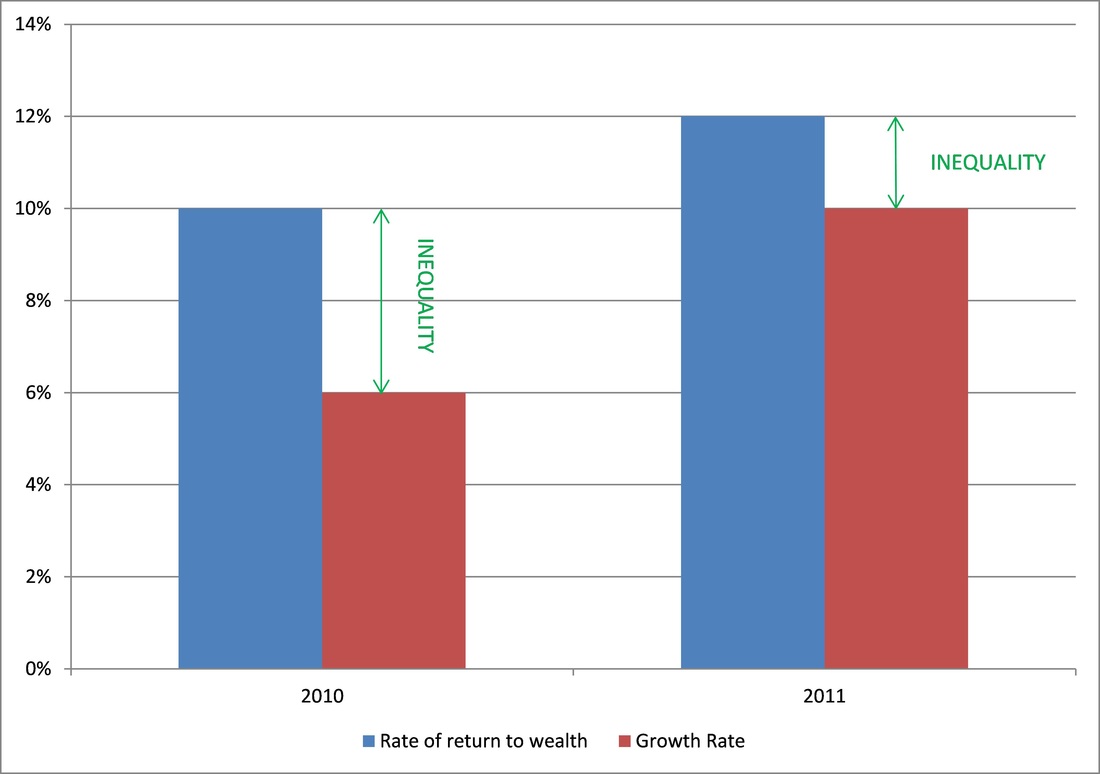

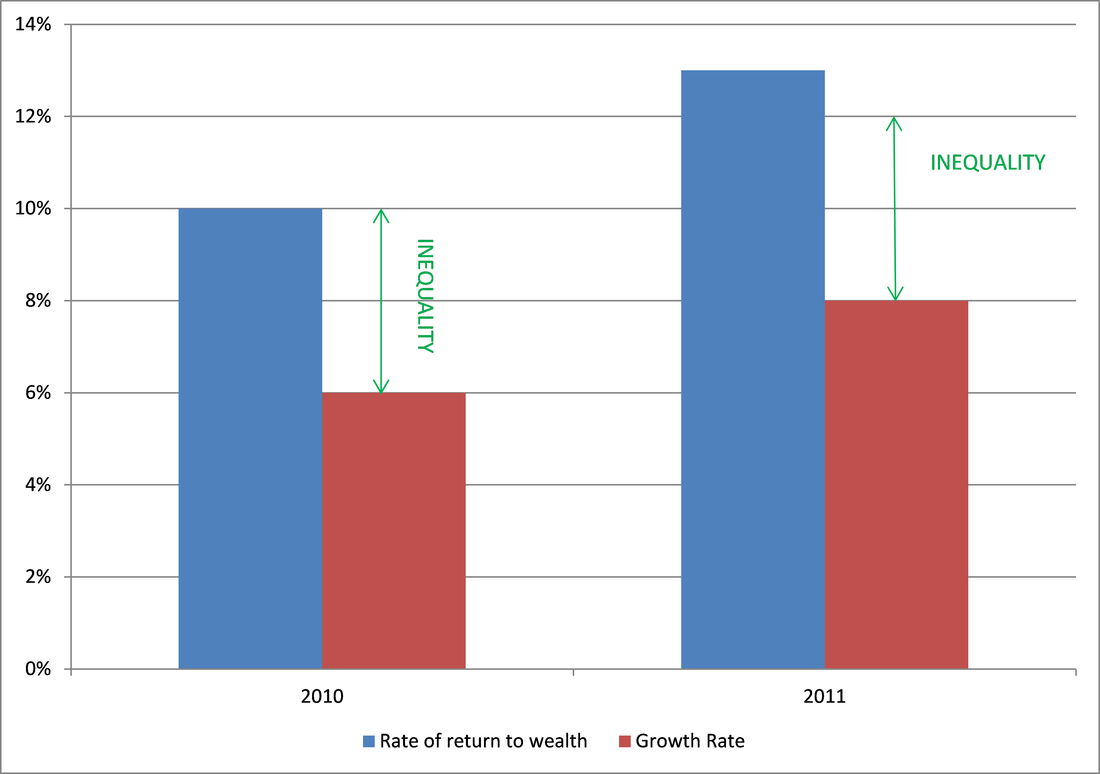

From here, Piketty outlines general patterns between wealth and growth. He explains that wealth grows faster than economic output in general, which represents in the expression r > g (where r is the rate of return to wealth and g is the economic growth rate). Ceteris paribus, “faster economic growth will diminish the importance of wealth in a society”, and the same vice versa. “Demographic change that slows growth will make capital more dominant”. However, it is only rapid growth or government intervention that will disperse the concentration of wealth, and prevent it from entering the patrimonial situation Karl Marx was worried about.

Mr. Piketty ends by saying that governments should step in now and impose taxes on wealth, lest it leads to soaring inequality or political instability.

Critics have question Piketty’s assertion that the future will resemble the past, arguing that returns to wealth decreases as the amount of wealth increases. They also add that today’s generations come upon wealth by working for it, rather than through inheritance. Furthermore, they question the feasibility of Mr. Piketty’s recommendations to governments, stating that they are ideologically, rather than economically, driven. Regardless, Piketty’s book as received major critical acclaim for its data gathering and analysis.

Key terms:

1) Welfare state: According to Brittanica, this is where the government plays an active role in taking care of the citizens of a state.

2) Return on wealth: This is the income from investing in wealth.

Context:

It is worth discussing Piketty’s idea of inequality. He discusses how r > g in general. He states that if the economy grows faster, then the importance of wealth will reduce, and if the economy grows slower, the importance of wealth will increase. This concept is illustrated in the diagrams below:

In the introductory blog post I had posted about this inequality series, one of the questions I said that would be discussed is the link between growth and inequality. According to Piketty, faster growth reduces inequality.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed