Click here to read the original article.

This article discusses the link between inflation and demography. Ageing populations leads to “slower growth, because a country’s potential output tends to fall as its labour force shrinks.” They also have to face heavier fiscal burdens because governments must provide for more pensioners from fewer taxes. Given its ageing population, this is a big problem for Japan.

Many economists take persistent deflation in Japan as evidence to show that prices fall when counties age, and consequently, growth slows. The Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, has tried disproving that link by increasing inflation through aggressive quantitative easing. However, as inflation has yet to reach the targeted 2%, the tempting conclusion is that ageing populations cause deflation.

Recent research has sought to disprove that link.

It is important to not just see the links between ageing and prices, but the way they cut. In terms of the factors of production, when growth slows, businesses reduce investment so that the cost of capital can decline. However, wages should rise when the supply of workers falls. And in terms of government action, some governments reduce their spending on other projects to support pensioners, causing slow growth and sluggish inflation. Other governments, however, may decide to monetize their debt, pushing inflation up.

The article disentangles all these possibilities to descry a clearer link between an ageing population and inflation.

This article states a few main points:

1) In a recent paper by Mr. Katagiri of the Bank of Japan and Mr. Konishi of Waseda University distinguished between an ageing population caused by lower birth rates and an ageing population caused by increased longevity.

a. Fewer births would lead to a smaller tax base, encouraging governments to “embrace inflation to erode its debts and thus stay solvent”. This will be further explained under ‘context’.

b. Longer lives would cause the ranks of pensioners to swell, along with their political influence. Their influence would augur for “tighter monetary policy to prevent inflation eating into savings”. This will also be explained under ‘context’.

Messrs Katagiri and Konishi believe that the latter (increased longevity in Japan) has caused deflation of about 0.6ppt over the past 40 years. Therefore, it is not just ageing that has caused deflation, it is more longevity.

2) This article then looks at the impact of ageing on financial assets. The “life-cycle theory” suggests that people average out their consumption over lifetimes: “going into debt when young, buying assets when their earnings peak and selling them to pay for retirement”. In theory, it should lead to lower asset values, but in practice, while house prices often fall, stocks rise.

One important aspect is whether the assets sold are domestic or foreign. Messrs Anderson, Botman and Hunt of the IMF found observed the decrease in Japan’s net saving rates from 15% to 0% of disposable net income from the 1990s to 2011. Many of these savings are invested in foreign assets, and when retirees repatriated their funds after selling stocks and bonds abroad, the yen appreciated. This, in turn, causes deflationary pressure by lowering the cost of imports. This can be negated by “strong monetary easing combined with a credible commitment to an inflation target”. In other words, Abenomics.

3) A recent paper by Messrs Juselius, and Takats from the Bank for International Settlements offers a vastly different explanation for how ageing affects inflation, pointing out that Japan may be quite atypical. They observed 22 advanced economies from 1955 to 2010, and found a steady correlation between deflation and demography, even though just the opposite is assumed. They found that a larger share of dependents is linked with higher inflation, while lower inflation is linked with a higher labour force. Their explanation for this is that countries that consume goods more than they produce them (i.e. with a smaller labour force) causes excess demand, and thus, inflation. However, countries that consume less than they produce causes excess supply, and thus, deflation.

This then begs the question of why Japan has such low inflation. Some possible explanations are damaged balance-sheets caused by the asset bubble pop in the 1980s, or the tentative and hesitant Abenomics.

Context:

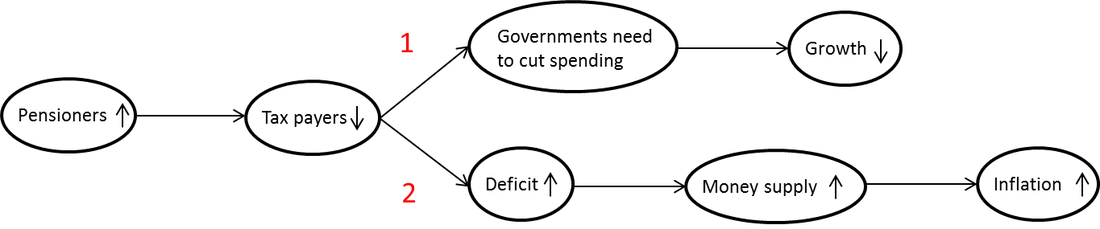

1) Why does the government need to make “painful cuts as pensioners multiply”? And what does it mean “monetise their debt”? Number 1 is for the former, and number 2 is for the latter.

3) In the section, ‘Greyflation’, the article discusses a finding that explains how a larger share of dependents is linked to higher inflation, and how fewer dependents mean lower inflation. I am sceptical about this argument because, if this were the case, what should we expect in the US when baby boomers retire en masse? A spike of inflation? This is contrary to what a lot of people believe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed