Click here to read the original article.

1. Click here to read the introduction post.

2. Click here to read the first post on asymmetric information.

Hyman Minsky

Hyman Minsky is best known for his work on what causes a financial crisis. His work remained unnoticed throughout his lifetime and for a long while after. This is, in large part, due to the fact that his work was not in conformity with mainstream economics. While the majority of economists believed that markets were efficient (explained under ‘Context’), Minsky argued that inefficiency is what causes financial crises, and called this hypothesis the “financial-instability hypothesis”.

The financial-instability hypothesis

This describes how “long stretches of prosperity sow the seeds of the next crisis”, according to The Economist.

First, Minsky defined investment as giving money in the present in return for getting money back in the future. For example, an ice cream machine is an investment. An ice cream parlor gives money right now to buy an ice cream machine. Due to the ice creams the machine produces, the firm gets money back in the future.

Where does the ice cream parlor get the money to buy the machine? It can get it from two sources: its own funds or others’ funds (e.g. the bank). The balance between the two sources is key to explaining financial instability.

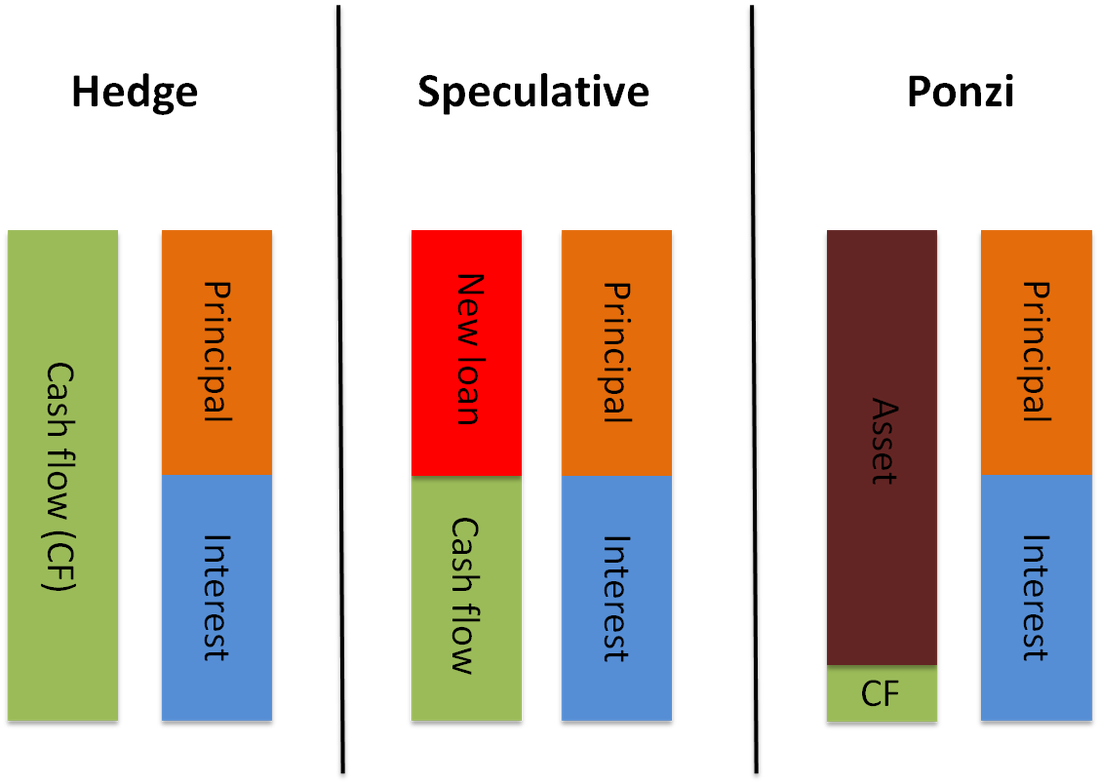

Next, Minsky describes three types of investments.

- Hedge financing: All of a firm’s borrowing is repaid with its future cash flow (explained in ‘Key Terms’). In order for this to work, a firm must have little borrowing and lots of profits. This is the most stable type of investment.

- Speculative financing: Cash flow covers interest payment but firms must roll over their debt to repay the principal (explained in ‘Context’). This is riskier than hedge financing.

- Ponzi financing: Cash flow covers neither principal nor interest; thus, a firm is forced to rely on the value of the asset to cover its costs (explained in ‘Context’). If the value of the asset falls, either due to contractionary monetary policy or an external shock, the firm will have to default.

These three types of financing are illustrated in the diagram below.

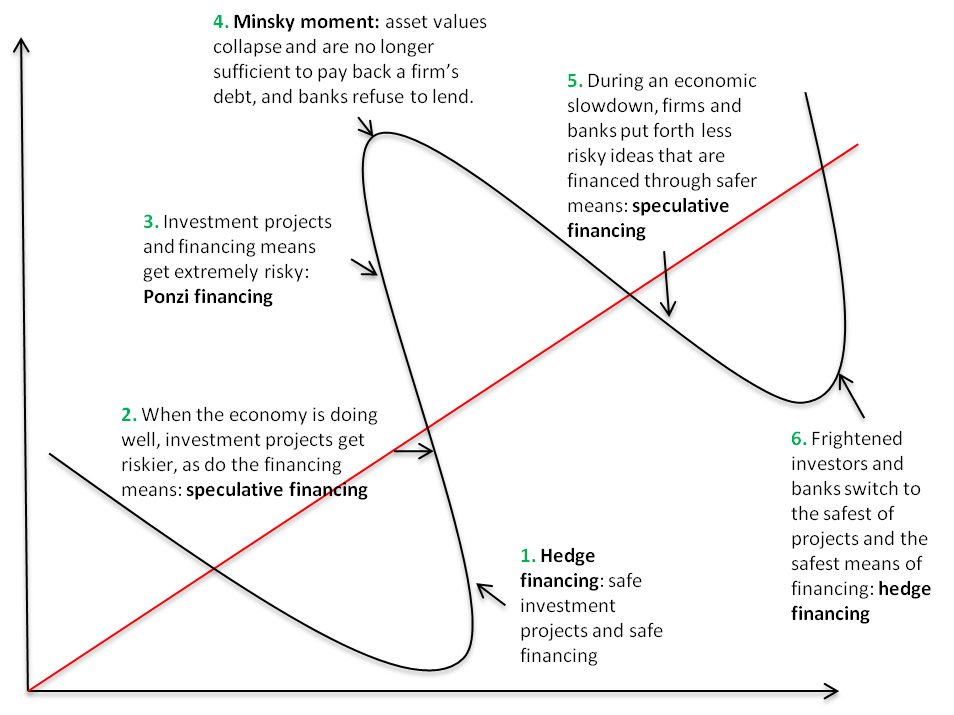

Thus, an economy dominated by hedge financing slowly becomes an economy dominated by Ponzi financing, and a drop in asset values leads to a financial crisis. In other words, economic stability breeds instability.

The point at which asset prices start plunging is called a “Minsky moment”, which is a term coined by PIMCO’s former chief economist Paul McCulley. A Minsky moment is now synonymous with a financial crisis. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

If we assume this to be the reason for a trough, then we can assume that even without any external shocks (such as government intervention or a war), the business cycle would occur.

Minsky today

At the time, Minsky’s work was disregarded. People believed that markets are efficient and stable. Now, behavioral economics has adopted the idea that markets are not efficient.

Minsky and the nature of economics

The financial-instability hypothesis explains a very specific situation in which a stable economy leads to an unstable economy due to increasingly risky investments and financing. This goes against the grain of economic theory, which aims to explain a general concept. Take, for example, the theory of demand, which states that for any normal good, the increase in the price results in a decrease in demand. Thus, the theory of demand explains a multitude of economic situations – the financial-instability hypothesis does not.

For this reason, mainstream economics ignored Minksy’s hypothesis. After his death, and after the financial crisis, his work gained popularity and relevance.

The implications of the hypothesis

The world is still shaken up by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and its aftermath. Investment is much less risky now than it was pre-GFC. But if we were to look at the future of the global economy using Minsky’s hypothesis, the conclusion is clear: economic actors will forget, or perhaps ignore, the warnings of the GFC in favor of riskier and riskier financing.

Looking further

Looking past The Economist article, there are some things worth mentioning.

The application of the Minsky moment can be seen in the financial world. Firms have to make two types of decisions: which investment projects are worth pursuing, and how to finance them (i.e., through their own funds or borrowed funds). As the economy picks up steam, firms start undertaking riskier projects and they also start financing them with more of borrowed funds. This eventually leads to a Minsky moment of instability.

The other interesting point about Minsky’s work is what generates business cycles, and why they are self-adjusting. Mainstream thinking follows Keynesian economics: peaks and troughs are determined by whether an economy is above or below full employment. Minsky provides an alternative explanation to why the business cycle is self-adjusting.

Key Terms:

Cash flow: The amount of money generated by a business.

Context:

1. What does “markets are efficient” mean?

This refers to a hypothesis called the efficient market hypothesis.

The efficient market hypothesis states that all the available information in a market is already reflected in the price. One of the implications is that it is impossible to “beat the market”.

For example, assume the price of Disney shares is $10 per share. Disney then releases the news that a new movie is coming out, and everyone reacts immediately by buying Disney shares in the hope that when the movie comes out, the value of the share will appreciate. The share now costs $11. When the movie actually comes around, the market would have already reacted to the news and the price of the share will stay at $11.

An individual might try to beat the market by investing in a share given new information, but ultimately, according to the efficient market hypothesis, he or she will not be able to.

2. What does it mean to roll over debt to repay principal?

A firm rolls over its debt by borrowing principal from another bank.

Suppose an ice cream firm borrows $100 to buy an ice cream machine from Bank 1. The interest rate at Bank 1 is 10% a year. Thus, after a year, the ice cream firm must pay $110 to Bank 1.

At the end of year 1, the ice cream firm has made $30. Thus, it still needs to get $80 from somewhere to pay back Bank 1. The firm goes to Bank 2 and borrows $80 at 10% a year. It can now pay back Bank 1.

At the end of year 2, the firm owes Bank 2 $88. If the firm has made $30 again during year 2, it must borrow again to repay the principal from Bank 2.

This is how a firm rolls over debt. In theory, as long as the profits exceed the interest rate, a firm will ultimately be able to pay back all its debt.

3. How would an asset cover a firm’s costs?

Selling off an asset would get a firm money, which it can then use to pay back the bank. If the value of the asset falls, then it may not be able to cover the principal or the interest rate it owes the bank.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed