Click here to read the original article.

This article discusses the problems with redistribution as a means to reduce inequality, i.e. taxing the rich to give to the poor. In economics, this works theoretically, as giving money to the penniless who will spend it immediately should boost consumption and GDP. However, if done wrong, this can cause more harm than good.

In 1920, the English economist Author Cecil Pigou argued that shifting purchasing power to the poor will do little to dampen the spending habits of the rich, but will boost output as the poor will immediately spend the money on necessity goods.

The argument rests on the assumption that the poor would spend more if they had the means and the rich would smooth over their spending patterns. To investigate this assumptions, Messrs Kaplan and Weidner of Princeton University and Violante of New York University used large microeconomic datasets to see household income and wealth across eight different economies.

They looked for families that lacked a buffer of liquid assets to offset short-term changes in income. These families were the ones who would theoretically spend immediately from a government windfall.

Herein lies the problem: this “hand-to-mouth” term is not so straightforward – many American households may not have liquidated assets, but do have large illiquid ones.

One reason why people are so short on cash is because of the housing debt. In America, those with small mortgages live less hand-to-mouth than those with large ones.

Another reason why is due to age. The research shows that those around 40 years old are most likely to be cash strapped.

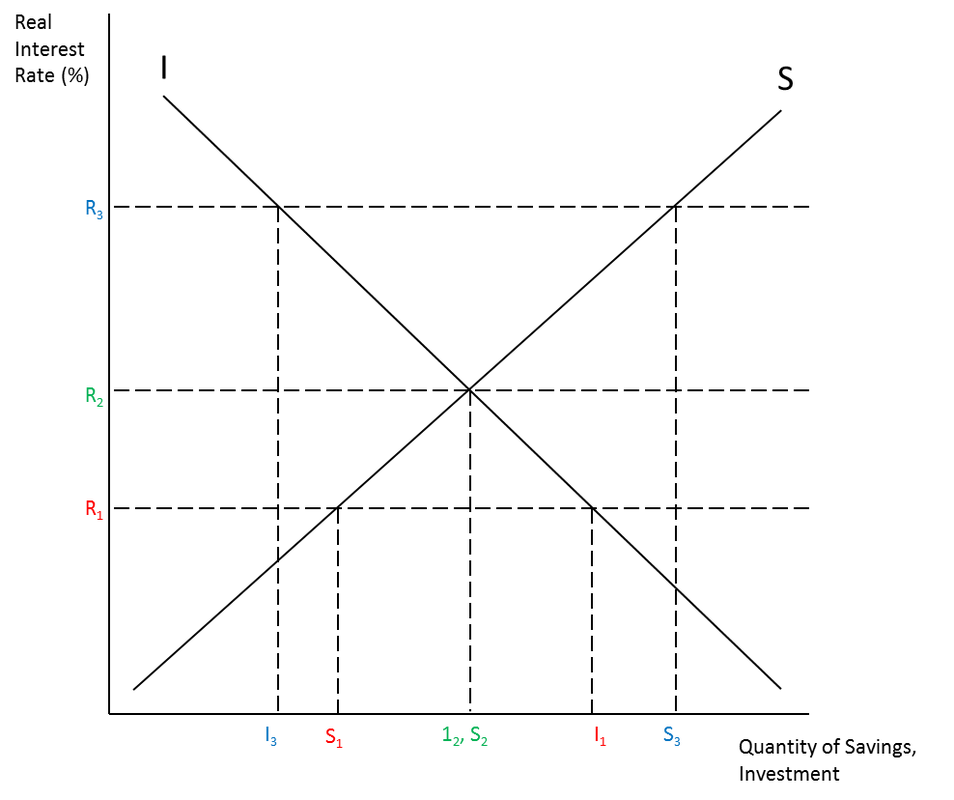

The findings show that “cash shortfalls affect behaviour”, in that those with high liquid wealth spend the least from an unexpected windfall, those living “hand-to-mouth” spend more, but it is those with lots of illiquid wealth but low income that spend the most. This links in with another study by Merrs Cloyne and Surico of Bank of Britons and London Business School respectively, which shows that “taxing those with illiquid assets could cause more of a fall in spending than previously expected”.

Yet another research paper shows that the assumption that the more a worker’s wages fall the more they support redistribution rises may not be true. In fact, support for redistribution has not changed, or has fallen, as inequality has risen.

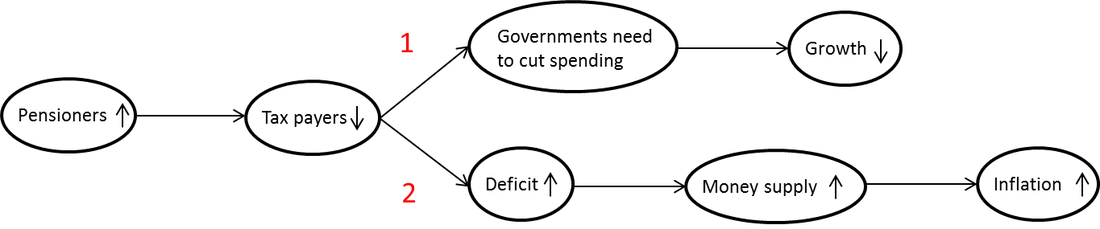

One major culprit could be age – those under 40 follow the predicted pattern but those over 65 do not, perhaps because when the survey was first conducted in the 1970s the now-65-year-olds were more cash-strapped, but they are not any more. (More on why they are not cash strapped is explained under ‘Context’.) They fear that redistribution would cut health benefits.

Overall, these findings show a few things:

1) Stimulus packages should also be aimed at the wealthy, too;

2) Taxes on the wealthiest should be phased to allow them to liquidate their assets, and;

3) Politicians betting on the popularity of redistribution among voters should realize there may be great aversion from the retirees.

Context:

1) It is worth reading my other blog post about why not to tax the rich, although it has nothing to do explicitly with inequality. This can be found here.

2) Why is it that “the chances of being wealthy but cash-strapped peak around the age of 40”? This has to do with the life cycle. The original research paper can be found here. The life cycle is explained in the previous blog post, which can be found here.

3) One question that is not answered is why “the wealthy-but-income-constrained react most, spending 30% of any windfall, suggesting they are even more cash strapped”.

4) It is important to remember for the previous point that there may not be a symmetry between windfall gains and sudden taxes or losses of income, i.e. people may not spend as much when they have windfall gains than they save when they are taxed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed