This article updates us on the economic health of the U.S. after the end of QE. While the author presents us with some encouraging statistics, such as an increase in employment and diminishing underemployment, other statistics are not as promising, such as a decrease in the labor force participation rate (LEPR) and stagnant wages. My guess is that the discouraging statistics will turn around in time, e.g. these statistics are the result of time lag.

D.K. also contrasts the generally positive economic outlook of the U.S with that of the EU, where expansionary monetary policy may be needed. Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB) is facing opposition from Germany, whose fear that expansionary monetary policy will result in hyperinflation stems from its past bad experiences with hyperinflation. It is worth referring to “Dwindling U.S. Inflation Casts Shadow”, which discusses the fact that, as opposed to hyperinflation taking place, there is minimal inflation at all.

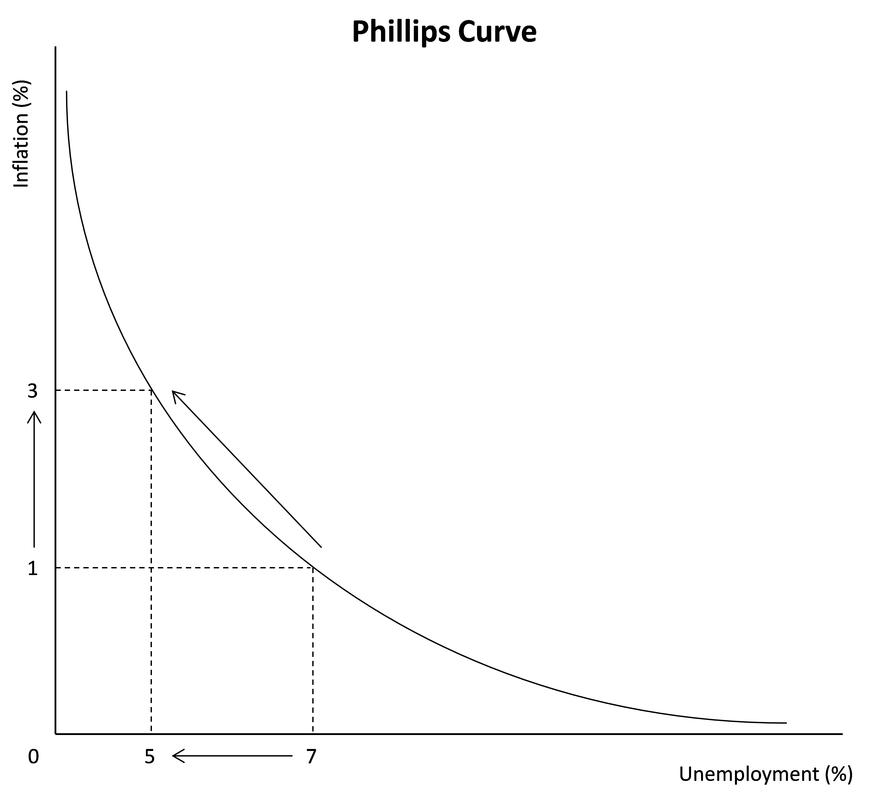

Pay attention to the statement in the fourth paragraph that says, “… unemployment reaches a level where employers have to start paying more to find workers”. The nature of having to pay more is one of the steps in the Phillips curve, which suggests a link between unemployment and inflation, chiefly that as unemployment is lowered, inflation increases. This relationship is shown below (figures not based on real data).

We will discuss this in later blog posts.

Key words:

Unemployment – This is when those who are actively looking for work cannot find an

Underemployment – Where a worker can find a job, but it does not maximize his capacity. Examples would include those who are only able to find a part-time job, or perhaps an economist with a Ph.D. working as a bus driver.

Hyperinflation – This is when the rate of inflation accelerates, sometimes out of control. One of the most famous examples is in Germany from 1921-1924.

PMI – This is the Purchasing Managers Index and measures the economic health of the manufacturing sector.

LFPR – The labor force participation rate is the ratio between the labor force (those who have a job or are actively looking for one) and the whole working age population. So, those who retire prematurely, for example, are no longer part of the labor force, but are instead part of the rest of the working-age population.

One important analysis point about the LFPR is to do with the rate of unemployment. Let’s say the unemployment rate drops. Does that mean that more people are finding jobs? Perhaps. But it could also mean that people have given up looking for jobs and, in a sense, have retired prematurely. So, the unemployment rate has dropped, but so has the LFPR. The point to remember is that a lower unemployment rate does not equate to a better economic situation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed