This article discusses the flaws with having on-off capital controls. Capital controls (defined in ‘Key Terms’) are, and have been, a big debating point. Currently, Russia is trying to soften the blow of the oil price’s plunge on the rouble by “imposing limits on currency conversions”, and Iceland is easing the restrictions on its capital controls after the financial crisis.

For a long time, capital controls were frowned upon, until 2012, when the IMF gave its stamp of approval, saying that it is okay “under certain circumstances”. Many argue that the problem with capital controls is that it “breeds inefficiency”, i.e. those who have excess savings cannot give it to those who need the money for investment. It is, they argue, a form of allocative inefficiency.

In the 1990s, when Mexico and Asia were faced with a sudden influx of cash, they realised that this influx led to uncontrollably high exchange rates and asset prices. Furthermore, when it finally exited these economies, it damaged financial stability.

Now, there is general consensus that capital controls are needed, and that they should be “targeted and limited”, such as having minimum stay requirements or taxes on short-term borrowing. Additionally, many believe that capital controls should be counter-cyclical, which is to say that when there is an influx of cash, controls should be tightened, but when there is an exodus of it, controls should be loosened.

While this solution may seem neat and tidy at first, there are three major underlying problems with it.

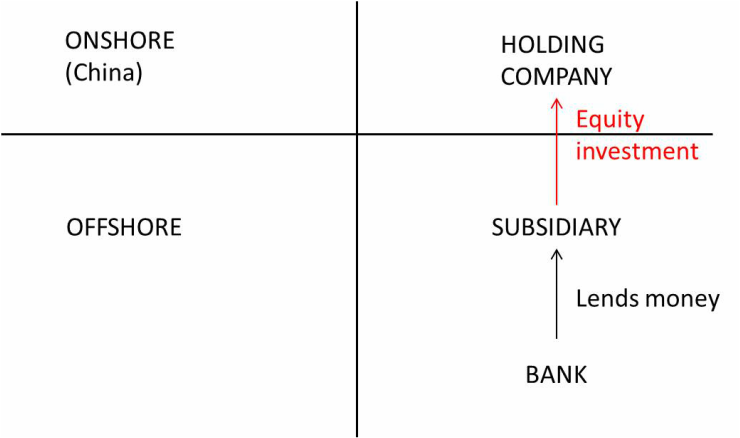

The first is that many can find ways around capital controls. One example of this is in China, which has very stringent controls, and little tolerance for short-term borrowing. Yet, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has found that, in June, international bank lending to China has reached $1.1tn. This is because many investors are sneaking around capital control laws by issuing debt via foreign subsidiaries, and thus, loans are being disguised as FDI. This point is explained in more detail in ‘Context’. Furthermore, as the amount of FDI going into China is already extremely high, it is not hard for firms to disguise loans as FDI; nobody will notice.

The second biggest flaw with counter-cyclical capital controls, i.e. on-off capital controls, is that it ignores the revealed preference of the countries. Records have shown that many economies prefer easing barriers to outflows.

Joshua Aizenman of the University of Southern California and Gurnain Kaur Pasricha of the Bank of Canada (quoted in the article) have studied 664 cases of changes in capital flows and have found that governments much prefer easing restrictions on outflows, which happened 274 times, substantially more than any other type of change. While, in theory, easing restrictions on outflows has the same effect as blocking inflows (net inflows decline), the former shows confidence in the economy through a looser leash on the economy.

The third point against counter-cyclical capital flows is that there is little relationship between capital controls and inflation or growth, i.e., they are not counter-cyclical. During the global financial crisis, in fact, some countries such as China and Indonesia loosened restrictions as their economy boomed, which is not counter-cyclical at all.

Furthermore, in 2009, Brazil tried increasing capital controls to slow down the real’s appreciation, by imposing taxes on debt and equity flows. In fact, the real appreciated at the same pace as before the capital controls were in place. Instead, as seen by the sudden increase in FDI, investors just found other ways to get the money past the barriers.

In all, while in theory counter-cyclical capital controls seem like a good idea, it is not so.

Key terms:

Capital flows: This is the flow of capital in and out of a country by investors investing in assets. For example, if the British economy is doing very well, investors in America would want to buy assets, e.g. houses, by trading in USD for GBP. This is an influx of capital. When the British economy is not doing as well, the American investors would sell the houses and trade GBP back for USD, which is called an outflow.

Context:

1. In 2012, the IMF gave its approval for capital controls under the correct situation. Before that, during the Asian Financial Crisis, the IMF had aided the damaged economies by giving them loans, under conditions that government spending decreases, taxes increase, etc., and that there were no capital controls. Malaysia’s Prime Minister at the time, Mahathir bin Mohamad, had disregarded the IMF’s terms, and imposed capital controls anyway to protect its economy. The result was that Malaysia recovered at around the same time the other countries did, but the Malaysian economy suffered much more during the Asian Financial Crisis. People who support capital controls often cite this argument.

2. What does the phrase “issuing debt via foreign subsidiaries” mean? First of all, a subsidiary is a company that is either partially (50%+) or fully owned by another company. With that in mind, this phrase can be best described by the diagram below:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed