Click here to read the original article.

This article discusses the ways in which Japan could improve its economic situation, chiefly through fiscal and monetary policy.

Krugman highlights aspects of the Japanese economy that are encouraging: “Output per working-age adult has grown faster than in the United States since around 2000, and at this point the 25-year growth rates look similar”, and “… Japan is closer to potential output than we are”. Nevertheless, Japan is struggling to escape from deflation. Why has Abenomics not worked as well as people hoped?

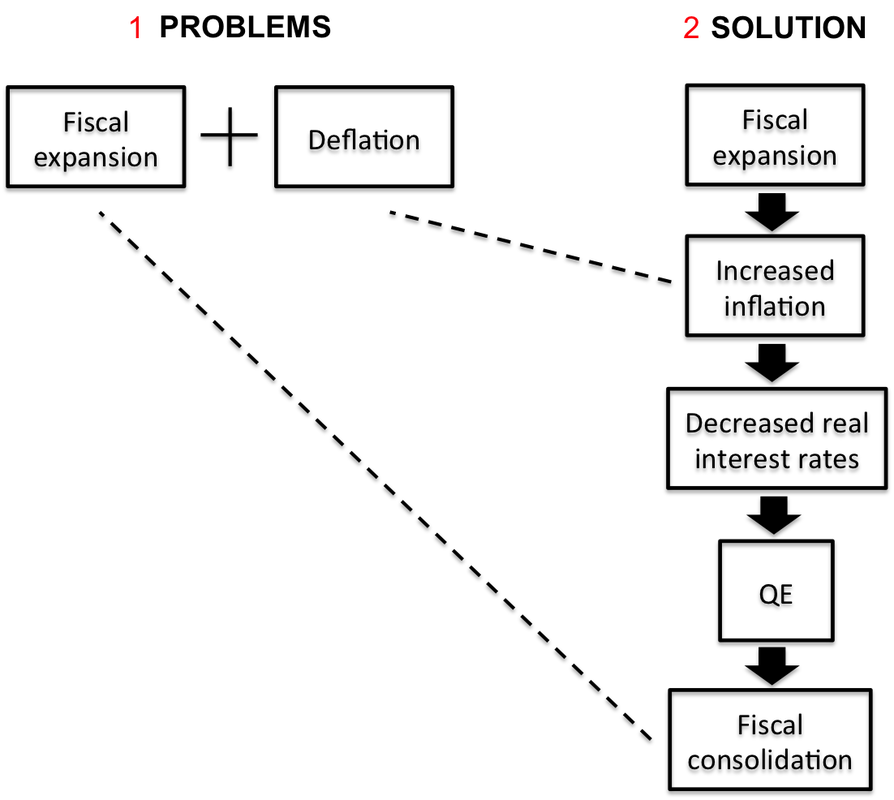

The main ideas in his article are best portrayed through a flow chart:

2. It follows that one of the only solutions is to raise inflation such that real interest rates fall. This way, QE can happen alongside fiscal retrenchment. Krugman adds as a side note that raising inflation would also reduce the value of debt.

Krugman describes how Japan may be facing a negative Wicksellian rate (explained under ‘key terms’) as a permanent condition. He points out that even if the Bank of Japan were to promise greater QE, it is ultimately consumer expectations of future inflation that will determine inflation (more about this will be explained under ‘context’).

Krugman’s solution is to combine monetary policy with a burst in fiscal stimulus. The fiscal stimulus will raise the inflation, and the increase in inflation leaves room for more QE. Only when more QE is enacted can fiscal consolidation occur, which would cut down the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The question, then, is how high should inflation be? While the answer does not have a certain numerical value currently (i.e. it has to be high enough to allow QE to occur), it is clear that Japan’s 2% inflation is not enough.

Krugman emphasizes the problem of fiscal consolidation alone: it may cause an economy slump, in which case Abenomics may be beyond redemption. He says that the only measure left is for Abe to engage in aggressive austerity and QE together to increase inflation.

Key terms:

1. Wicksellian rate (a.k.a. natural rate of interest): Kurt Wicksell was a leading Swedish economist who was best known for his idea of the natural rate of interest. The theory suggests that there is a long-run natural rate of interest, and if the current rate of interest is higher than said natural rate, there will be deflation, and if the current rate is lower than the natural rate, there will be inflation. When the current interest rate equals the natural rate of interest, there is equilibrium in the commodity market and price levels are stable. To read more about this (and how it pertains to modern-day economics), click here.

Context:

1. To understand this article, it is important to understand what Abenomics is. Abenomics is a portmanteau of the words economics and Abe – Shinzo Abe being the Prime Minister of Japan. His plan is to fire three ‘arrows’ to stimulate economic recovery. The first arrow is expansionary monetary policy in the form of QE, the second is fiscal stimulus, and the third is structural reforms, mainly through strengthening the Japanese army.

While these three arrows seem like feasible ways to revive the economy, Japan is still faced with lacklustre inflation, and many attribute this to the fact that Abe is not aggressive and hawkish in any of his three tactics, or arrows. Paul Krugman discusses what Abenomics’ next steps are.

2. How does future inflation determine inflation today? Consider this situation: a consumer in an economy wants to buy a new phone. She believes that inflation will increase in the future, i.e. the price of the phone will be higher in the future than it is currently. For this reason, she buys the phone today. Many consumers in the economy also believe that future prices will be greater than current prices, and buy the goods and services today instead of waiting for the price to increase. The aggregate demand in an economy suddenly increases, and producers increase the price of the goods and services in an economy as a response. This increase in prices of goods and services is, in fact, inflation. Deflation works in a similar way. In this way, inflation (or the lack thereof) is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

3. In my opinion, there are a few problems with Krugman’s proposed solution. The first is that despite years of fiscal expansion by the Bank of Japan (BoJ), deflation still persists. Even aggressive fiscal expansion, which is what Krugman suggests, has its problems. Firstly, there is no telling when the aggressive expansion will result in a sufficient level of inflation; it could take much longer than the BoJ can afford, and it will exacerbate the debt-to-GDP ratio greatly. Secondly, even when the BoJ deems the inflation level in Japan as healthy enough to allow fiscal retrenchment to happen, they have to be wary of consumer expectations. Either the BoJ will have to execute fiscal consolidation so slowly that it now faces high inflation and a high debt-to-GDP ratio, or it will have to carry out fiscal consolidation quickly enough to avoid inflation from becoming a worry. The problem with the latter is that consumer, investor and producer confidence in the market is shaky enough as it is; fiscal consolidation may scare them enough to revert the economy back into the original state of deflation where people are hesitant about consumption, production and investment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed