Click here to read the original article.

1. Click here to read the introduction post.

2. Click here to read the first post on asymmetric information.

3. Click here to read the second post on the financial-instability hypothesis.

The Stopler-Samuelson theorem discusses the relationship between trade and wages. The theorem suggests that free trade is not always a mutually beneficial scenario.

Stolper and Samuelson

Wolfgang Stolper was an American economist best known for his work on the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. Paul Samuelson is one of the most celebrated economists and is hailed the father of neo-Keynesian economics.

Free trade, comparative advantage and the Heckscher-Ohlin model

Free trade is usually seen as a mutually beneficial scenario. This idea can be traced back to classical economist David Ricardo, who is well-known for his work on comparative advantage (explained under ‘Context’). Comparative advantage is seen as a solution to the labor scarcity problem, where some countries do not have enough labor for a certain industry, and some countries have too much. Heckscher and Ohlin together advanced the comparative advantage theory, stating that the country that faces labor scarcity (in the Heckscher-Ohlin model, this country is the U.S.) should specialize in those industries that require little labor, and leave the industries that require lots of labor to other countries that find no shortage of workers.

Most economists believe that workers, as well, would be better off from free trade. Some people argued that scarcity gives workers more bargaining power; eliminating scarcity would leave workers worse off as their nominal income would decrease (explained under ‘Context’). However, nominal income would also increase due to free trade, as would purchasing power (explained under ‘Context’). Thus, free trade benefits workers as well.

Further, labor has the benefit of being versatile. Thus, if one industry relies more on capital and less on labor, in the long-run, workers can always move to another industry that is more labor-intensive.

In both the comparative advantage theory as well as the Heckscher-Ohlin model, both countries and workers participating in trade are better off. Thus, conventional economic wisdom is that free trade is always mutually beneficial.

The Stopler-Samuelson theorem

Stopler and Samuelson both disagreed that free trade is always beneficial for workers.

While he worked in Nigeria, Stopler noticed that textile workers were usually too tired, inexperienced or sick to work productively; consequently, the industry required a 90% tariff to compete (explained under ‘Context’). He lamented about the quality of labor there, stating that if such a high tariff was needed, it wasn’t worth having the industry at all. This was the basis for the Stopler-Samuelson theorem.

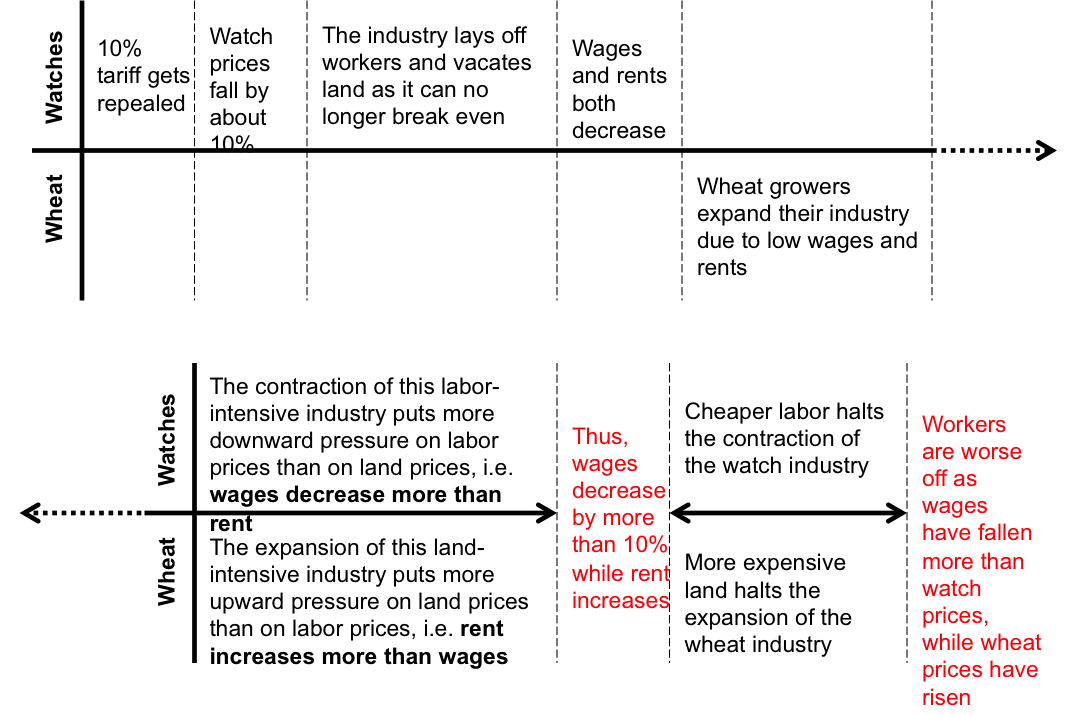

Consider a country that has lots of land but little labor. The country makes only watches and wheat, where the former is labor-intensive and the latter is land-intensive. Suppose the watch industry has a 10% tariff to compete. The Stolper-Samuelson theorem says that if the tariff gets repealed, workers will suffer. The theorem is demonstrated in the timeline below.

Variations on the theory include splitting workers into skilled and unskilled labor in an industry, say, watches. The dynamics work similarly: free trade decreases the prices of watches, and the unskilled workers’ wages decrease while the skilled workers’ wages increase.

What the Stolper-Samuelson theorem is missing

The Stolper-Samuelson theorem does not answer a multitude of questions. For example, the assumptions of the Stolper-Samuelson model are questionable. First, it is a large assumption that a country produces everything, e.g. watches and wheat. Some countries might just produce watches, and some might just produce wheat.

The theorem also assumes that both markets are perfectly competitive, and that there are constant returns to scale. Not many industries follow those assumptions.

The importance of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem

Undoubtedly, the theorem is not directly applicable; given its multitude of assumptions, the theorem in its simplest form is only pertinent in a few circumstances. Stolper himself treated the theorem with great caution, stating that it is only a “slight theoretical possibility” and that many other economists would look at “more realistic concerns”. So why is this theorem so groundbreaking?

The theorem shows that free trade is not always beneficial. Economists had earlier approached the topic of free trade with the attitude that nobody would lose. The Stolper-Samuelson theorem shows that free trade does not always have winners. The theorem is an inconvenient iota of truth to those who insist on looking only at the benefits of free trade.

Extra reading

To read a real-life example of the theorem, click here.

While there is no free version of the original paper online, you can access it here for US$40.

Context

1. What is comparative advantage?

To understand comparative advantage, it is important to understand absolute advantage first.

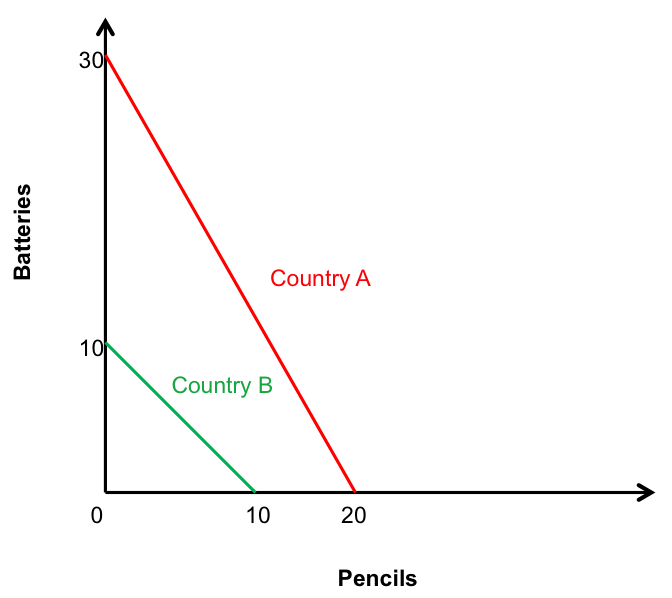

Assume two countries, A and B. Both countries produce batteries and pencils. In one hour, A can produce 30 batteries or 20 pencils. In one hour, B can produce 10 batteries or 10 pencils.

Regardless of whether A produces batteries or pencils, it will produce more of them than B can. Thus, A has the absolute advantage over B. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

As a general rule, a country that has a PPC lying completely above another country’s PPC has an absolute advantage in production.

Comparative advantage looks at the opportunity cost of producing batteries or pencils for either country. In this example, A can produce three times more batteries than B can, and two times more pencils than B can. Thus, A should produce only batteries as it is more efficient in producing batteries, i.e. it has the comparative advantage in batteries. As David Ricardo said, the country should produce what it is “most better” in. B should produce only pencils as it is the “least worse” in producing them.

A and B would then trade to get whatever quantity of batteries and pencils they require. If they do so, then both countries would get more of each good than if they did not trade.

With comparative advantage, A will produce 30 batteries, and B will produce 10 pencils. Totally, 40 goods will be produced.

Without comparative advantage, assume A makes 10 pencils and 15 batteries, and B makes 5 pencils and 5 batteries. Totally, 35 goods will be produced. In fact, if we take any two points on both PPCs, total production will be less than if both countries specialized using comparative advantage.

2. Why would scarcity provide workers with more bargaining power, and why would less bargaining power decrease a worker’s nominal income?

Scarcity is an extremely important bargaining tool. Suppose, in an industry, there are 100 employers and 5 employees, i.e. employees are scarce. If one employer offers an employee $50 a day, another employer, desperate for that employee, will offer them $70 a day, and so the price of the employee will be bid upwards.

Suppose, in another industry, there are 100 employees and 5 employers, i.e. employees are abundant. If one employee offers to work for $50 a day, another employee, desperate for a job, will offer to work for $30 a day, and the price of the employee will be bid down.

Thus, scarcity gives you bargaining power, in that workers can ask for more money, and less bargaining power bids a worker’s nominal income down.

3. Why would free trade increase a worker’s purchasing power?

Purchasing power is how much someone can buy for a fixed amount of money. For example, imagine that in Country A, with US$1, you can buy five chocolates. In Country B, with US$1, you can only buy two. Workers in Country A thus have a higher purchasing power.

Assume free trade does reduce a worker’s nominal wages as their bargaining power decreases. But the price of imported goods would also decrease. So the workers would be able to buy more of those imported goods with their wages, i.e., their purchasing power increases.

4. What does it mean that an industry requires a 90% tariff to compete?

In Nigeria there was a 90% tariff in the textile industry. That means that imported textiles had to pay 90% import duties to the government before they could be sold in Nigeria. Hence the domestic producers could price their products 90% higher and still compete with imports.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed